by Ian Pomerantz

Published April 24, 2023

From the 17th century onward, choral music became the defining feature of the musical identity of Western Sephardic Jews

In about 1724, a young Italian composer ventured into the Jewish Ghetto and visited its resident Sephardi, Ashkenazi, and Italki scuole, or synagogues, to listen to their respective liturgies. Far from a mere wanderer, Benedetto Marcello was a part of a new breed of musicians that were the forerunners of today’s ethnomusicologists. And Marcello was looking for something among the Jews of Venice, the Republic of which he was a citizen: Antiquity.

From the music he heard, some of which was for solo hazzan, some congregational, and some, he says, for choirs of men and boys, Benedetto published eight volumes of solo, instrumental, and choral works over the next four years, each tome decorated with a woodcut of King David playing his harp.

What Marcello captured over time was a snapshot of the beginnings of Sephardic choral music, a tradition that is now four centuries old. The first choral compositions to emerge from the Sephardic community stem from the beginnings of the Western Sephardic (or Spanish and Portuguese) Diaspora in Italy in the 17th century, not long after their flight from Portugal, centered around the cities of Livorno and Venice. Unfortunately, most of these early works do not survive, but what does come down to us exhibits a fusion of cantorial intonation of text with contemporary Italian polyphony.

The first major choral works, however, come from Amsterdam, when these Sephardic Jews from Italy, along with others coming straight from Iberia and southwestern France, settled in the Netherlands. In 1639, they united to form a community called Kahal Kados Talmud Torah. In 1675 they inaugurated their new building with a grand spectacle lasting several days.

The building still stands and is known today simply as “The Esnoga.” For the occasion, a new multimovement choral cantata was composed by anonymous members of the congregation in the Italian Baroque style, harkening back to the Italian origins of its composers. The cantata, called Shir Hanukat Beit HaKenesset, or “Song for the Rededication of the House of Meeting,” sets poetry by the Esnoga’s own Portuguese-born Rabbi, Isaac Aboab de Fonseca, and survives in a manuscript of the 18th-century cantor Joseph ben Sarfati.

Nothing like it had ever existed before. Scored for a cantorial soloist, a choir of men and boys, and a Baroque chamber orchestra, it displays to both the Jewish and Gentile public the cultural achievements and prestige of the Portuguese-Israelite Congregation. The cantata has likely only been performed twice: at its 1675 premiere in Amsterdam and in 2019 by the Jerusalem Baroque Orchestra.

Over the next century, the Amsterdam community would continue to commission cantatas/oratorios, two of which survive. In 1774, the community commissioned Italian (and non-Jewish) composer Cristiano Giuseppe Lidarti to write a Hebrew oratorio in the gallant style popular in Amsterdam at the time about Queen Esther, which was the centerpiece of Purim celebrations at the Esnoga that year, and which has seen renewed performance since 2000.

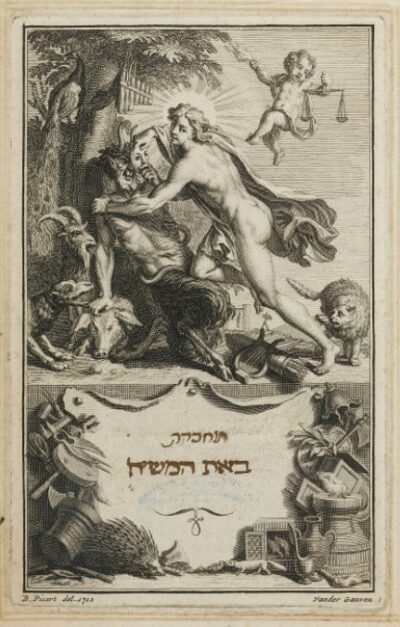

The second oratorio, B’iath HaMashiach, or “The Coming of the Messiah,” was written as a Jewish response to Handel’s ubiquitous oratorio Messiah. The music for this tantalizing second piece has been lost, as has any record of its performance and reception at the Esnoga, but the decorated libretto survives in the collection of Etz Haim Library.

It was clear from the very beginnings of the Amsterdam community, in the 17th century, that choral music was to be the defining feature of the musical identity of Western Sephardic Jews. The Portuguese community of Amsterdam founded its own Talmud Torah for the education of boys and young men. This educational institution also served as a choir school, providing young musicians with a solid music education in which they learned the basic elements of musicianship, the fundamentals of singing, and the liturgy of the community.

This arrangement served multiple purposes. It guaranteed a permanent musical presence in the synagogue. It provided a laboratory for new composers to have their works performed. Most importantly, it ensured that the musical traditions of the congregation were transmitted intact to the next generation of congregants and Jewish leaders.

On Sabbath, Festivals, and community events these boys would provide choral music for the services along with a choir of men, who were, except on Sabbath, accompanied by harp continuo and obligato flute, violin, and cello or viol. The community sponsored its own composers-in-residence who were also active members of the congregation, such as Abraham Cáceres (fl. 1718-1740), who left behind a full catalogue of music.

These community composers would continue to add to the repertoire of the Amsterdam Esnoga over the years, responding to musical changing tastes of Western Europe. In the 19th Century, these disparate influences eventually converged in a complete collection of liturgical choir music for the year called the Santo Serviço, sung by an in-residence professional choir of the same name, which continued to operate until most of its members were murdered in the Holocaust. However, there have been multiple efforts to revive the choir’s activity, and today a layman’s choir sings the repertoire several times a year.

The Western Sephardic Diaspora expanded across Western Europe and the Americas during the 17th through the 19th centuries, founding communities from London to New York, and from Newport to the Caribbean. Each of these new communities developed their own unique choral traditions, rooted in a common Western Sephardic idiom as native composers in each city added their own voices to the repertoire.

Sephardic choral music first crossed Jewish inter-ethnic divisions, however, in early 19th-century Hamburg, Germany, when members of the Portuguese-Israelite Holy Congregation of Sephardim of Hamburg and the Ashkenazi German-Israelite Community of Hamburg established a new congregation they called The New Israelite Temple Society. This was to be the foundation of the Reform movement.

The committee appointed two Sephardic cantors, Joseph Meldola and Joseph Piza, to establish the new musical identity of the community, and the integrated Spanish and Portuguese melodies and borrowed heavily from the Sephardic aesthetic of noble formality and gravidade. These melodies, alongside those of Salomon Sulzer, became the musical standard across the Reform world as more congregations in Europe and the Americas joined the Reform movement, and they would remain so until the widespread acceptance of compositions by Louis Lewandowski in the 1880s.

It would be mistaken to assume that Sephardic choral music is exclusive to the Spanish and Portuguese world. The 18th and 19th centuries saw choral traditions established in the Eastern Sephardic cultural sphere as well, especially in Turkey and the Balkans. Both the Sephardic communities of Sarajevo, Bosnia, and Bucharest, Romania had Sephardic Temple Choirs of around 20 boys, directed by the Hazzan in each community, who sang harmonically.

Their repertoire is little-known and little-studied. No major study has ever been done on the choral music of the Sarajevo Sephardic congregation, and the Marele Templu Sefarad Cahal Grande of Bucharest was looted and burnt down by the Iron Legionnaires on the night of January 21, 1941, during the Bucharest Pogrom along with all its paper archives. Its ruins and remaining associated buildings were then bulldozed by Ceaucescu in 1985.

The training of Hazzanikos also took place in Izmir and Istanbul in a choral setting, overseen by the Chief Hazzan. However, this training differed from Western and to some extent Balkan Sephardic choral music. In the West, the choral texture was polyphonic, where different melodies interweave with each other, or homophonic, in which a primary melody is supported by one or more voices to create functional harmony. In Turkey, the textures were mostly monophonic, in which all voices sing a single melody, or heterophonic, where multiple voices sing different, often florid variations of a melody, which is the most common type of texture in traditional Turkish synagogue singing when more than one voice is involved. This style emanated directly from Turkish maqam singing and Ottoman classical music.

Indeed, many of the composers, instrumentalists, and Hazzanim who were playing music in the Turkish synagogues were also masters of Ottoman classical music at the Ottoman Court and Topkapi Palace—so much so that a culture of musical reciprocity developed between Jewish Hazzanim and their liturgical choirs, local Turkish Mevlana ensembles, and the Ottoman court in the 18th and 19th centuries, giving birth to the Maftir genre.

Today, there are several active Sephardic choral groups in Turkey—notably in Istanbul, the center of Eastern Sephardic choral singing. Some, like Yako Taragano Synagogue Hymns Choir, focus on the traditional liturgical and paraliturgical ensemble singing described above, and seek to document and preserve these synagogue hymns as well other facets of Eastern Sephardic liturgical culture.

Others, as has been traditionally the case, aim to play a role in the musical and Jewish education of the community’s next generation, both for their own enjoyment and serve to transmit this intangible musical legacy to a new generation of Sephardim. The foremost among these new (and now co-educational) children’s choirs is Las Estreyikas d’Estambol, directed by Izzet Bana.

Izzet and Las Estreyikas were recently featured in the Netflix series Kulüp—announcing that Sephardic choral tradition is thriving in the 21st century and finding new platforms to share this precious tradition.

A version of this article was first printed in the newsletter of the Sephardic Brotherhood of America, El Ermano Sefaradi, Winter 2023.

Ian Pomerantz is a bass-baritone and co-founder and co-artistic director of Les Enfants d’Orphée. He studies Jewish cantorial music at Abraham Geiger Kolleg at the University of Potsdam in Germany. He is a past member of EMA’s Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Access (IDEA) Taskforce.