by Jacob Jahiel

Published February 27, 2023

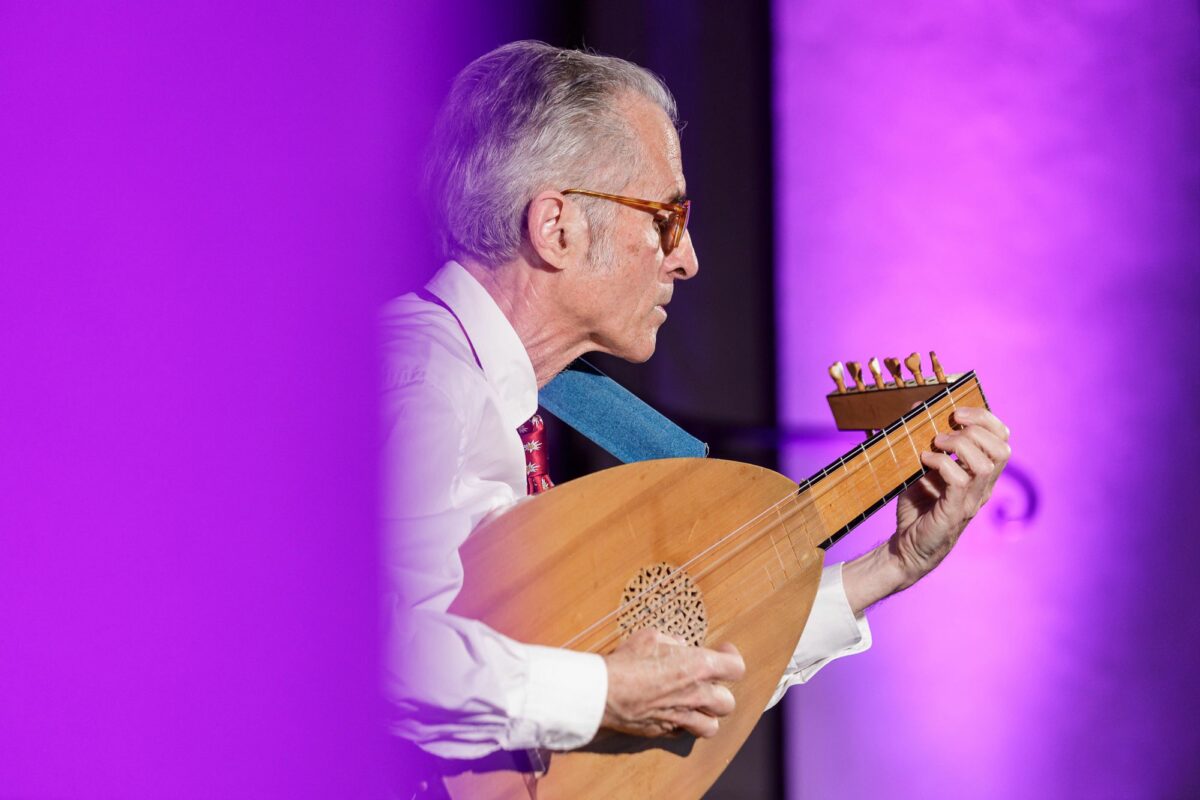

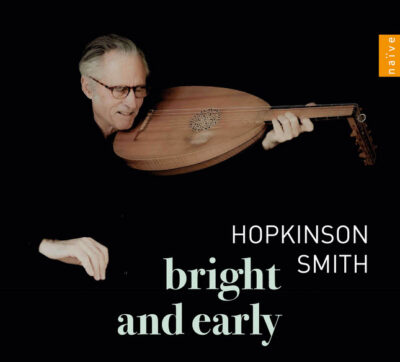

Bright and Early, Hopkinson Smith, lute. Naïve Classiques E7545

Revising someone else’s music is a dangerous business but, in the cases of lute virtuosi Francesco Spinacino (fl. 1507) and Joan Ambrosio Dalza (fl. 1508), and for two entirely different reasons, someone had to do it.

The manuscripts containing Spinacino’s intabulations, for one, contain questionable accuracy. Despite having been printed by the otherwise fastidious Ottaviano Petrucci, the Intabulaturo de lauto libro Primo and Libro Secondo (1507) are riddled with odd phrases, missing material, questionable counterpoint, and more than the occasional misprint. As they stand they are, in effect, unplayable.

In a phone interview, lutenist Hopkinson “Hoppy” Smith described spending hours poring over Spinacino’s music, “trying to find some spark of life in the compositions.”

“Some open up naturally,” he told me, “they might have a little stumbling block here and there. Others, I felt, I had to do some corrective surgery.”

For instance, Smith describes Ricercar No. 23 as a piece that is “basically monothematic with a two-voice theme at the beginning. But when it becomes a single voice, the bass is missing. So I added the bass and added some measures to give it balance.”

On this new recording, on the French Naïve label, Smith opted to craft an introduction for Ricercar N0. 12, offering “a fanfare of the mode leading into the part we have from Spinacino” and to “clarify the more meditative, almost narrative style.”

In the most abstract terms, “narrative” seems an apt descriptor of Smith’s delicate treatment of Spinacino’s rich and varied ricercars, a genre named from the Italian word “to seek” or “to search.” Accordingly, even notated ricercars should impart a sense of extemporaneity and fantasy. In Smith’s hands, Spinacino’s ricercars unfold organically and with a clear sense of forward momentum, much like a good story. His sense of time is supple but never slack, balancing both spontaneity and architecture.

While Dalza’s works are less cerebral than Spinacino’s—the program booklet describes him as “more the café and tavern lutenist”—Smith performs them with undeniable charm and bounce. Yet they pose their own set of problems: the simplicity of Dalza’s intabulations indicate “a little bit of a rush job.” The composer likely agreed, promising a subsequent edition with added difficulty for more adept players. He never kept his promise, so Smith applies an impressive arsenal of diminutions to the original tunes.

For instance, Dalza’s “Piva alla ferrareze” contains frequent repetition of musical material that demands elaboration. Conceiving of the dance as a sort of “country music piece,” Smith tosses in a “little banjo section” in addition to a sundry of other ornaments and textures. As a result, repeated material never grows tiring, but neither does the musical scaffolding risk collapse under the weight of his diminutions.

While a little ornamentation is not likely to get Smith into trouble, he makes no apologies for his more substantial interventions, and it is true that making a few tweaks is a far more palatable option than condemning a repertory to obscurity.

And, anyway, his “corrective surgery” seems minimally invasive much of the time—while he may have polished Spinacino’s rough edges and injected intrigue into Dalza’s tunes, he still celebrates the delightful idiosyncrasies of both composers. It is clear that changes were made not from condescension, but out of admiration for the music’s potential, a potential that is beautifully rendered in this album. (And check out a recent video interview with Hopkinson Smith in EMA’s Trailblazers in Historical Performance series.)

One final detail finds itself at the end of this review not out of lack of importance, but simply because it stands apart—an octave string has been added to the third course (pair of strings) in addition to the standard fourth, fifth, and sixth, shifting the registral balance to the middle and treble ranges. Moreover, the top octave string rests on the more prominent thumb side, adding brilliance to the high notes and producing what sometimes feels like micro-syncopations. The result is mildly disorienting but entirely delightful.

Jacob Jahiel is a writer and viola da gambist living in Montréal. He was a 2022 Rubin Institute for Music Criticism Fellow and is a recent graduate of the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University, where he received an M.A. in musicology with an outside field in historical performance.