by Steven Silverman

Published January 22, 2024

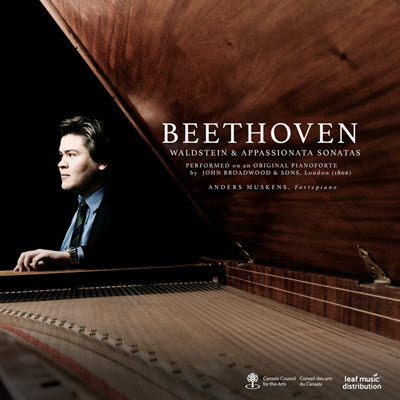

Beethoven: Waldstein & Appassionata Sonatas. Anders Muskens, Fortepiano. Leaf Music AM202303

Beethoven’s Waldstein and Appassionata sonatas are beloved and iconic, and it’s no small feat that Canadian fortepianist Anders Muskens makes them sound not only vital and exciting, but new and revolutionary.

His fortepiano is especially interesting. Made in London in 1806 by John Broadwood & Sons — a year or two after these sonatas were composed — the instrument was restored by Paul Kobald in Amsterdam in 2022. Beethoven owned a similar instrument, but only at a time when he could no longer hear it.

Muskens’ instrument on this recording has plenty of resonance — leather hammers notwithstanding — and its decay is noticeably longer than a Viennese fortepiano’s from that period. We hear a pronounced difference in registers. The lower bass is plangent although the pitches are not always distinct, allowing notes in this register to be played with a lot of vehemence without getting strident.

Muskens makes good use of this in the return of theme in the first movement of the Appassionata (Op. 57) when the accompanying bass suddenly shifts to repeated tritones. The middle register is baritonal and rich. The top is a bit weak but allows for ethereal colors. These coloristic possibilities are augmented by an una corda pedal that can shift to one string or two strings (a moderator effect) or transition from 1-2-3 strings to produce a crescendo effect. An audible and telling instance is in the final variation of the slow movement of Op. 57 where the una corda on one string produces an ethereal, harp-like color which preserves the movement’s serene affeckt (notwithstanding all of the thirty-second notes buzzing around).

He also daringly uses una corda in violent, virtuostic passages, for example in the sonata’s finale exposition in the extended section in the upper register just after the modulation to C minor (and in the parallel spot in the recapitulation). His “Wow! What was that?” color change gives welcome timbral variety and contributes to the forward momentum.

But for all the interest in the instrument, the Broadwood is just part of the newness and excitement of these readings. Muskens’ playing is technically impeccable. The octave glissandi (played triumphantly, rather than pp as appearing in most editions) and extended trills of the Waldstein (Op. 53) finale are enviably clean, as is the extended passage with both hands in sixteenth triplets leading into the final prestissimo (which prestissimo is taken at a properly vertiginous clip). Repeated single notes (as in the Op. 57 opening movement) and repeated chords (such as the Op. 53 first movement main theme) are always properly spaced and don’t sound notey. The difficult accompanying figures in alternating thirds and octaves in the Op. 57 finale, which can sound labored, here is a properly surging quasi tremolando. The thorny canonical passages in that movement are likewise right there.

Muskens is especially sensitive to changes of mode. The long sequence in triplets in the development section of the first movement of the Waldstein, which can be a dull slog, here comes vibrantly to life with a new color and mood, with subtle tempo adjustments, for each of the modulations: C – F – B-flat – E-flat minor – B minor.

He makes a lot of interesting tempo and rubato choices, going beyond such standard choices as relaxing the tempo of the second theme groups. He goes in for a lot of rhetorical effects which mostly work: occasional pauses; taking the interjected ff chords in the Appassionata first movement theme well out of tempo; a big, broad tempo for the final chords of the Waldstein. One effect, not completely successful to my ear, was slowing the tempo and softening the dynamic in the climactic passage just before the recapitulation in the Appassionata opening movement. Although Muskens’ reading interestingly gives some feeling of pathos rather than the usual (notated!) heaven-storming pandemonium, I think the version of ff without slackening and a sudden piano at the return of theme works better — although the artist points out that the subito piano appearing in modern editions was not in original published versions.

Scholarship likewise supports some of his other seemingly unusual interpretive choices. Muskens rolls some of the chords in the second theme group of the Waldstein first movement, a notation which appears penciled into the 1805 edition. There are also a bunch of minor differences in note readings. One endearing new note is playing high Cs rather than high A-flats before the final plunge downward in the coda of the Appassionata finale. In an email exchange, the artist explained to me that this was not an intentional reading, but was done in the heat of the moment and left in because the take was otherwise so good. Three cheers for preserving verve and spontaneity!

One minor quibble. Muskens properly takes all repeats, but does them all identically or near identically. For example, taking a long, amorphous pedal at the start of the Appassionata finale’s development section was arresting and surprising the first time, but lost its surprise when hearing it identically on the repeat. For an artist as imaginative as Muskens, I would have hoped for some differing perspectives the second time through. (But see the cartoon in The New Yorker magazine of a pair of aristocrats grumbling while listening to Beethoven play the piano, the caption being “He’s taking all the repeats again.”)

Muskens’ new Beethoven recording, released as a CD and audio stream last month, demands to be heard. Highly recommended.

Steven Silverman is a pianist and harpsichordist whose performances include concerts at Weill Hall in New York City and the Salle Cortot in Paris. He and his wife, the violinist and violist Nina Falk, are co-founders of the Arcovoce Chamber Ensemble, now in its 24th season.