by Anne E. Johnson

Published November 13, 2023

The innovative, cross-cultural work of this Jewish, early-Baroque composer is more relevant than ever

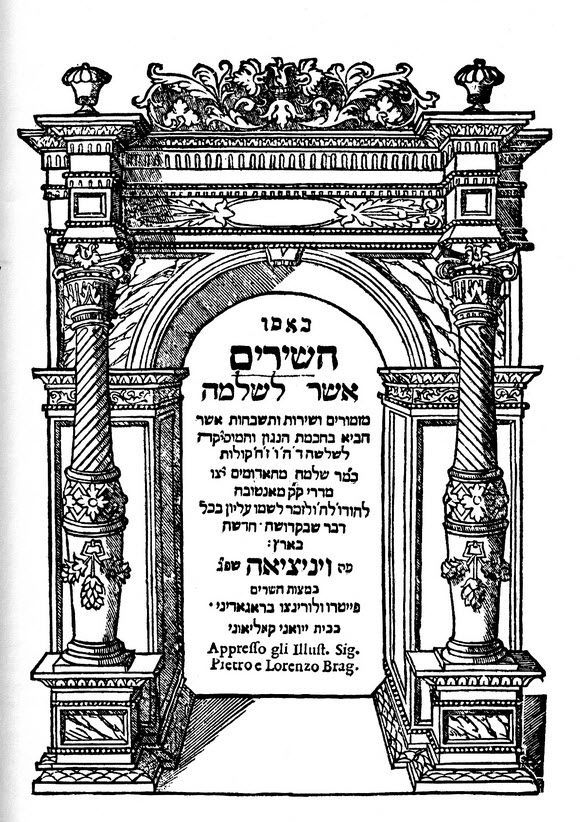

In 1623, Salamone Rossi, a musician at the court of Duke Gonzaga in Mantua, published a set of 33 Psalm-settings in Hebrew using techniques of Italian vocal polyphony. In the synagogue, this new music, HaShirim Asher LiShlomo (typically translated as Songs of Solomon), was a matter of some controversy; 400 years later, it’s still controversial. Its musical value, however, is not up for debate.

The San Francisco-based Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra and Chorale will acknowledge the 400-year milestone on December 4 with a program they first presented in 2015, Jews & Music: Songs of Solomon.

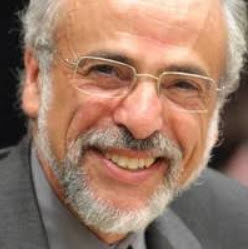

While the war in Israel and Gaza rages on, the innovative, cross-cultural work of this Jewish, early-Baroque composer seems more relevant than ever. The topic of early Jewish music can be rife with emotion, especially now. One specialist on Jewish early music, Ian Pomerantz, spoke to me just a few days after the October 7 attack by Hamas against Israel. A bass-baritone, he’s sung Rossi’s HaShirim many times over the years, and although he’s not performing in the Philharmonia’s Jews & Music program, he’s followed the project closely. He began by commenting, “My perspective has changed, and I think the needs of Jewish communities and the early-music movement have changed overnight.”

The Philharmonia’s Jews & Music: Songs of Solomon program was developed, in part, by UC-Berkeley’s Francesco Spagnolo, a scholar of Jewish music, in collaboration with then-music director Nicholas McGegan. Spagnolo, now the Philharmonia’s scholar-in-residence, has worked with the orchestra on several projects, lately with its current music director, Richard Egarr.

When the Philharmonia’s Rossi project began, Spagnolo presented the first of many controversies: “They were looking at Rossi according to the mainstream narratives,” particularly those of Don Harrán, a musicologist at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem who died in 2016. Harrán’s scholarship and editions of Rossi have shaped how HaShirim is understood and performed.

An essential departure from that mainstream is Spagnolo’s conviction “that non-Jews went to synagogue inside the ghettos.” In performance, the Philharmonia uses an eight-person choir, prepared by Valérie Sainte-Agathe, with the Hebrew text and translation projected onto a screen. Spagnolo sits onstage, explaining his interpretation of HaShirim as an “adaptation of Hebrew prayers through the ears of an intercultural group that also includes non-Jews.”

Not everyone shares this perspective on Rossi. Joshua R. Jacobson is founder and director of the Zamir Chorale of Boston and curator of https://www.jewishchoralmusic.com/, an archive of articles (many by Jacobson himself) and other materials on Jewish music, emphasizing Rossi.

While Jacobson has not seen evidence that Rossi’s Christian colleagues knew his synagogue music, he does acknowledge that Rossi’s work could sometimes be heard outside of worship: “There’s evidence in some diaries of Jews of the time that they sang these pieces just for fun in their homes, including a woman, a rabbi’s wife. That would never have taken place in the synagogue.”

Within the synagogue, some Jews were less than pleased with Rossi’s polyphony. But Rossi had on his side Rabbi Leon Modena, an influential and complex figure, to defend his work against conservatives objecting to his Christian-inspired sounds. Jacobson sees the nay-sayers as a minority voice: “Modena was reflecting a certain spirit of the times where Jews wanted to participate in the Italian Renaissance culture.” The presence of Jews (not just Rossi) and their adapting of non-Jewish cultural concepts in the Gonzaga court is another sign of the zeitgeist. “This could only happen in places where there was a liberal enough attitude on the part of the Christian population to allow the Jews to do this,” Jacobson says.

Modena (1571-1648) wrote “a handbook for non-Jews to understand Jewish rituals,” explains Spagnolo, which he interprets as revealing the rabbi’s enthusiasm for Rossi’s experiment. “It describes the sound landscape of the ghetto in Venice. When Modena comes to the sounds of Italian Jews, he says this is the least elaborate, the least sonically appealing. So there might have been a conscious choice to enhance the sounds of the synagogue.”

Rossi’s most famous colleague at the Gonzaga court was Claudio Monteverdi, and Philharmonia Baroque includes Monteverdi on the concert program. Jacobson rates Rossi’s polyphony “on a par with any of Monteverdi’s madrigals.” Nevertheless, there is no evidence that the two composers actually knew each other.“They were on the same payroll, but they may not have met as far as we know,” Spagnolo says. “Or it could have been that Rossi was just a fiddler playing for Monteverdi’s compositions.”

Like Monteverdi, Rossi considered publication as a part of the composition process. The printing of HaShirim at the Bragadina Press in Venice bolsters Spagnolo’s argument that this work bridges cultures: “Jews were not allowed to own printing presses, but there were printing presses in Venice that specialized in Hebrew books where Jews worked as editors.” However, Bragadina did not print music. “So it’s a fair assumption that Christian music printers had to be called in to help with the musical layout of the page. Jews would have been involved in printing the Hebrew. The press was a known place of encounter.” Knowing that about the score, Spagnolo insists, is an element of historical performance.

Despite the high-quality Bragadina edition, “it was never reprinted,” says Jacobson. “We have to assume that it was fairly isolated. It wasn’t until the 19th century that we find a full flowering of polyphony in synagogue music.”

Still, Jacobson sees traces of Rossi’s later influence in an Italian synagogue chant for Psalm 80, verse 4, Elohim hashivenu, which bears a striking similarity to the canto part in Rossi’s setting of the same verse. “Did Rossi actually use a traditional synagogue chant?” wonders Jacobson. “I concluded that it’s probably the opposite. That it [the Rossi] became well known, and then the congregation adapted it and turned it into a congregational melody.”

Early Jewish music specialist Pomerantz, artistic director of Les Enfants d’Orphée, agrees that Rossi’s impact on Jewish liturgical music may be deep-seated. He cites the work of scholar Matthew Austerklein, claiming that “part books and prints of Rossi’s work made their way to Prague and informed the birth of what was to be the modern cantor and modern art music in the synagogue.”

When Pomerantz attended Westminster Choir College, he was one of only three Jewish students in his class. “It really forged my Jewish identity, and I started to pursue my Sephardic heritage.” In the intervening decades, he has sought out and recorded little-known Jewish music, including Rossi’s. “I’m seeing our current period reflected in the music of the past. It feels like I am discovering new parts of my story and new parts of myself, and I think there are a lot of people in my community who are doing the same.”

The liturgical aspect of the HaShirim is of paramount importance to Pomerantz: “I love singing his music in a liturgical context. To see him not as an early musician or historical performer but as a cantor.” The context within the service makes a difference, Pomerantz finds. “Are the congregants sitting or standing? I see how much of a text-driven composer he is. The liturgical placement of his Bar’chu, for example, gives me a whole new perspective on how he approaches the setting of words and harmony and his knowledge of Hebrew.”

The tendency for performers to ignore the liturgical aspect frustrates Pomerantz, who wishes Rossi’s Psalm-settings would be seen as more than just Jewish madrigals. “When we actually see them at work in a community or a synagogue, they turn into something different. I think we’re only getting half the story.”

The ghetto and cross-pollination

The liturgical context can have a practical impact on performing the work. Jacobson was baffled by Rossi’s use of double bars, a symbol used in Christian music to indicate when the choir stops and the priest or congregation takes over. He applied this theory to Rossi. “I found some traditional Italian Jewish synagogue chants from roughly 100 years ago. I inserted those, and it was like pieces of a puzzle fitting in.” His Zamir Chorale now performs those chants interpolated between Rossi’s sections.

Plenty of other performance-practice puzzles remain. Most prominent is the issue of text underlay, combining left-to-right music notation with right-to-left Hebrew words. Originally, the music was printed in the usual way, and each word was right-to-left, but the order of the words progressed left-to-right. Showing which syllables go under which notes was impossible (a problem familiar to singers of medieval music in any language).

Spagnolo’s concept of text underlay was changed by his philological research. “The Hebrew transcriptions in the scores of Rossi’s music interpret Hebrew according to the modern pronunciation.” Instead, he says, “All your vowels need to be Italian vowels. In Italian, the length of the vowels is sometimes different, and that length needs to be accommodated by going over more than one note.” Among Spagnolo’s sources for this hypothesis is a bilingual but homophonic poem by Rabbi Modena. “It sounds almost the same in both languages, but it means two different things.” There are also field recordings as late as the 1950s that “show continuity in this pronunciation.”

Continuity is an essential element for bass-baritone Pomerantz. “In early music we are ourselves revivalists,” he says, whereas “Jewish music schools have an unbroken tradition.” He envisions meaningful HIP discoveries from that untapped resource. “There are at least three schools of Jewish sacred music in the United States and several unions of Jewish sacred musicians. These aren’t being utilized at all.”

“Right now in early music,” Pomerantz continues, “non-Jewish performers are working without the creative involvement of Jewish communities. It’s very presumptuous for a [non-Jewish] early musician to say, ‘We have rediscovered your tradition, now let us come to the synagogue or the concert hall and present it for you.’”

For Spagnolo, a historically informed performance of HaShirim should focus on aspects of theatricality. “Aside from the linguistic connection,” he says, “the synagogue itself could be considered a theatrical space just like the court was.” It’s that parallel, Spagnolo says,that inspired non-Jews to go to the synagogue. “Christian humanists discovered that what they called the Old Testament had been originally written in Hebrew. Synagogues were, for Christian scholars, like a theological and liturgical Jurassic Park. They expected to hear how the Bible had been chanted at the time of the Christ.”

The ghetto is key to the cross-pollination of Jewish and non-Jewish ideas as well as Italian Jewish creativity, Spagnolo believes. In his view, the ghetto represents “the first time in Italian history where Jews were allowed to have a permanent or semi-permanent resident status within the boundaries of a city.” He calls it “a place that has porous walls. The sounds of the ghetto can be heard from outside the ghetto. And vice versa. What was happening in the synagogues in the ghettos in the 1600s was almost a proto-Enlightenment.”

The intercultural aspect of Jewish early music continues, says Spagnolo. Another of his Philharmonia programs explored the relationship of Handel’s first English-language oratorio, Esther, with that of Cristiano Giuseppe d’Arte, a non-Jewish composer using a Hebrew translation of Handel’s libretto, which was written mostly by John Arbuthnot. Spagnolo points out that some of the subscribers to Handel’s oratorios in London were Sephardic Jews.

“So we have a lot of non-Jews writing music for the synagogue,” says Spagnolo. Jacobson, for example, has published an edition of Cantata Ebraica, a 1680 Hebrew work by Carlo Grossi, a non-Jew. (And there’s plenty of Baroque music by Jewish composers besides Rossi. “The great repository of Jewish Baroque music is the Amsterdam and London communities,” says Pomerantz. He recommends the digitized holdings at Amsterdam’s Ets Haim Library. “They have music of Italian Jews and of immigrants. There are entire oratorios and cantatas starting from the mid-17th century.”)

For all the conflicting priorities and opinions among scholars and performers, there’s no controversy about the overall goal: getting this music performed. “The Rossi motets are not just of historical interest,” says Jacobson. “These are really good pieces of music.” He also points to Rossi’s innovation beyond the synagogue. “Rossi was the first to publish trio sonatas and also madrigals with basso continuo accompaniment. That is significant.”

Spagnolo finds that Jewish music tends to be marginalized in concerts. When he brought a group of Israeli cantors to sing at the Ravenna Festival, “they were listed under ‘world music,’ not ‘liturgical music.’”

As Jacobson puts it, “You’re doing Monteverdi? A concert of early Baroque music? Throw in some Rossi.”

Hopefully Spagnolo’s work with Philharmonia Baroque will bring more attention to Rossi and spark conversations about Jewish early music: “It’s about re-tuning our heads and our ears and rethinking the context.”

Anne E. Johnson is a freelance writer based in New York. Her arts journalism has appeared in the New York Times, Classical Voice North America, Chicago On the Aisle, and PS Audio’s Copper Magazine. She teaches music theory and ear training at the Irish Arts Center in Manhattan. Her latest writing for EMA discusses TENET Vocal Artists’ 15th season.