by Karen Cook

Published December 22, 2017

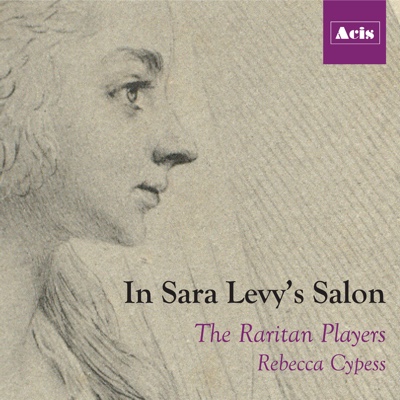

In Sara Levy’s Salon

Raritan Players (Rebecca Cypess, director)

Acis APL00367

CD REVIEW — Today’s high esteem for J. S. Bach’s music is usually credited to Felix Mendelssohn, who at age 20 “revived” Bach by conducting the St. Matthew Passion in Berlin. Yet recent research by scholar-performer Rebecca Cypess shows that Bach’s music had never disappeared. In fact, it was preserved and performed, along with that of his sons, in the private salon of one of Berlin’s most important patrons: Sara Levy.

Levy (1761–1854) was born into one of the richest, most influential Jewish families in Prussia. Her father, Daniel Itzig, was one of Frederick the Great’s “court Jews” (bankers); as such, she and her 12 siblings received an education befitting their social status. Levy was quite musically inclined, and her father arranged for her to study with Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, under whose watchful eye she excelled. She developed her private salon not only by obtaining or even commissioning new works, such as by Wilhelm’s brother Carl Philipp Emanuel, but also by collecting older works in antiquarian fashion. Her collection expanded to include compositions for flute for her husband as well as hundreds of other pieces, ranging from solo keyboard works all the way to keyboard concerti with full orchestra (which could have been comfortably performed in their salon). At least 500 scores stamped with her name, including some later used by Felix, were donated to the Sing-Akademie in Berlin when she retired, but we can assume there were many more.

Levy (1761–1854) was born into one of the richest, most influential Jewish families in Prussia. Her father, Daniel Itzig, was one of Frederick the Great’s “court Jews” (bankers); as such, she and her 12 siblings received an education befitting their social status. Levy was quite musically inclined, and her father arranged for her to study with Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, under whose watchful eye she excelled. She developed her private salon not only by obtaining or even commissioning new works, such as by Wilhelm’s brother Carl Philipp Emanuel, but also by collecting older works in antiquarian fashion. Her collection expanded to include compositions for flute for her husband as well as hundreds of other pieces, ranging from solo keyboard works all the way to keyboard concerti with full orchestra (which could have been comfortably performed in their salon). At least 500 scores stamped with her name, including some later used by Felix, were donated to the Sing-Akademie in Berlin when she retired, but we can assume there were many more.

Posthumously, Levy was overshadowed by the fame of her great-nephew Felix, and also by the hazards of World War II: the Nazis hid her collection, which was then taken by the Soviet Union. A team of musicologists, however, were later able to negotiate its return to the State Library in Berlin, where it now resides. She was also unrepentantly Jewish in an era in which many Jews converted, at least superficially, to Christianity; her role in the “Bach revival” was likely downplayed due to later German disinclination to recognize Jewish contributions to culture.

Levy’s contexts are described in precise detail in Cypess’s liner notes, which are but one stellar facet of this recording. Every composition here is somehow related to Levy’s family or personal collection, and in some cases is known only from Levy’s salon. The sheer historical value of the album is immeasurable, but its musical value is certainly no less. The opening quartet by Quantz, for example, introduces the listener to the warmth of the album’s acoustics and the vibrant, infectious interplay between the various instruments heard throughout. Steven Zohn’s traverso is marvelously rich, especially in its lower registers, marking the Quantz and the J. S. Bach Trio in E-flat major as particular standouts.

The two-keyboard arrangement of the other J. S. Bach trio, though, is simply mesmerizing; the contrasts in timbre between harpsichord and fortepiano highlight startling new depths, and the final C. P. E. Bach Allegro is wrung dry of everything from grandiosity and pathos to flashes of wit and humor. The ensemble treats every piece on this recording with such intimate care that it is easy to imagine the fascination, even joy, Levy might have felt playing this music herself.

Karen Cook specializes in the music, theory, and notation of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods. She is assistant professor of music at the University of Hartford in Connecticut.