by

Published July 21, 2017

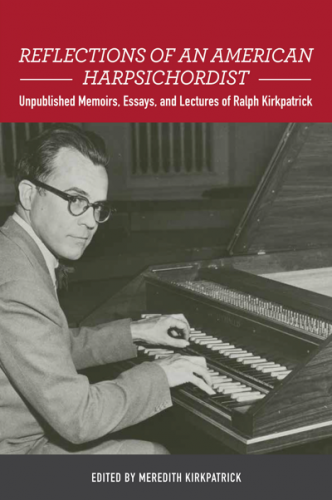

Reflections of an American Harpsichordist. Unpublished Memoirs, Essays, and Lectures of Ralph Kirkpatrick. Edited by Meredith Kirkpatrick. University of Rochester Press, 2017. 199 pages.

By Mark Kroll

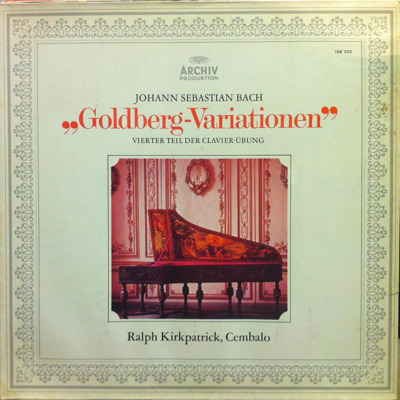

BOOK REVIEW — The life and career of Ralph Kirkpatrick is, in many respects, the story of a pivotal period in the history of the harpsichord during the 20th century. Beginning with his performances of music by Orlando Gibbons and J. S. Bach in 1930 as a Harvard University junior and of Bach’s Goldberg Variations in his senior year, both on the university’s Dolmetsch-Chickering harpsichord, Kirkpatrick would go on to become America’s foremost exponent of the instrument and its music as a performer, teacher, editor, and scholar for the next 50 years. He recorded the complete works of J. S. Bach twice, first on harpsichord and then on clavichord, toured worldwide (venturing as far as Egypt and Africa), and contributed an impressive body of scholarship that included a definitive biography of Domenico Scarlatti.

Kirkpatrick’s niece Meredith published a fascinating collection of her uncle’s letters in 2014; the current volume offers an additional and perhaps deeper perspective on Kirkpatrick as a scholar-performer. The book is divided into four parts: “Memoirs, 1933-77”; “Reflections,” in which Kirkpatrick writes about performing, recording, chamber music, and the travails of moving, tuning, and repairing harpsichords; six “Essays” on a variety of topics; and “Lectures (Yale University, 1969-71)” on Scarlatti’s harpsichord, sources, early-music performance, and other topics. Three appendixes feature a list of publications by and about Kirkpatrick, and a discography.

Kirkpatrick’s niece Meredith published a fascinating collection of her uncle’s letters in 2014; the current volume offers an additional and perhaps deeper perspective on Kirkpatrick as a scholar-performer. The book is divided into four parts: “Memoirs, 1933-77”; “Reflections,” in which Kirkpatrick writes about performing, recording, chamber music, and the travails of moving, tuning, and repairing harpsichords; six “Essays” on a variety of topics; and “Lectures (Yale University, 1969-71)” on Scarlatti’s harpsichord, sources, early-music performance, and other topics. Three appendixes feature a list of publications by and about Kirkpatrick, and a discography.

The memoirs reveal Kirkpatrick’s keen and often scathing observations about the harpsichord world, delivered in that unique style all his students remember well. (I studied with him from 1969-71: see “Lessons With Kirkpatrick” on my website: http://www.markkroll.com/autobiographical-reminiscence/). To cite a few examples, Kirkpatrick tells us: “The endless and endlessly profitable and unsatisfactory performances of Bach concertos…obscured the distinction between performance and prostitution,” and that he “hated” both the process of recording and the very material of the records themselves, which appears “to be totally useless. Printed matter at least can serve for lighting fires [and] equipping outhouses.”

Although Kirkpatrick initiated and directed a highly successful series of concerts in the Governor’s mansion of historical Williamsburg from 1938 to 1946, he had nothing good to say about the tourists “who came to lull themselves in dreams of an eighteenth century that never really existed” or the town itself, in which “everything is immaculate…there is no horse manure in the streets; the town jail is vermin-free, and if any odors at all can be detected, they are those of Ivory soap.”

Such bon mots aside, Kirkpatrick’s description of the people he met and with whom he worked opens a window onto much of 20th-century cultural history. We encounter Francis Poulenc, Igor Stravinsky, Elliott Carter, Eugene Ormandy, Isaiah Berlin, Bernard Berenson, Bruno Walter (with whom he performed St. Matthew Passion in 1940), Paul Hindemith (they played Biber’s “Mystery Sonatas” together in 1942), and the young Herbert von Karajan, who conducted Kirkpatrick’s performance of Bach’s D-minor harpsichord concerto in Salzburg in 1937. A completely unexpected appearance in this story is made by Billie Holiday, for whom Kirkpatrick performed Bach’s G-minor English Suite in his living room while she “put away the better part of a bottle of rum,” although “her face registered everything; no manifestation of the music seemed to escape her.”

Kirkpatrick’s programs at Dumbarton Oaks in the mid-1940s were also notable. They included all the Brandenburg concertos and Handel concerti grossi, five Bach harpsichord concertos and all the violin sonatas, Mozart sonatas, Mozart and Haydn trios, Mozart and Haydn symphonies, and eight Mozart piano concertos “played on a modern approximation of a piano of Mozart’s time.” Stravinsky conducted two of these concerts.

Kirkpatrick’s recounting of his touring experiences during the early days of harpsichord recitals is particularly hair-raising. Since there were so few instruments available, he often shipped three different harpsichords at the same time to make sure each arrived for a concert and was required to serve as tuner and repairman nearly as often as performer. He describes one instance in which he tried to fix a harpsichord in front of the waiting audience, “lying flat on my back in full evening clothes with screwdriver in hand and looking like an over-dressed garage mechanic.”

Kirkpatrick was a master teacher, albeit a demanding one. He joined the faculty of the Yale School of Music in the 1940s and recalls that pupils dubbed his “regularly scheduled teaching day in New Haven” as “Black Friday.” Indeed it could be! The transcriptions of lectures in this book (all of which I attended, and in which I heard him play musical examples on various 18th-century harpsichords) give another glimpse into his erudition and interpretive insights, such as the use of subtle gradations in articulation to express both the consonants and vowels of a work.

There is much more vintage Kirkpatrick in this book, making it essential reading for anyone interested in the harpsichord, scholarship, and musical style. Congratulations and thanks to Meredith Kirkpatrick for making this material available to us all.

Mark Kroll recently returned from China, where he performed, taught and lectured in Beijing and Shanghai. He is recording the complete pièces de clavecin of F. Couperin for Centaur Records.