by Kyle MacMillan

Published December 17, 2023

Aston Magna Festival celebrates 50 years

As long-time director Daniel Stepner plans retirement, Aston Magna will start auditioning candidates to run the festival for the next half-century

The Aston Magna Music Festival just might be the American early-music scene’s best-kept secret. The annual event, which marked its 50th anniversary in the summer of 2023, stakes a claim to being the oldest period-instrument festival in the country — among other significant firsts. Yet it remains largely unknown outside of Massachusetts and New York, where it rotates its performances among three small venues.

The festival’s longevity is partly explained by smartly keeping to its own lane, playing to its communities, making the concert experience intimate, with its own distinct personality.

Those in the know have nothing but praise for the organization, which presents five sets of chamber concerts each summer as well as other scattered events throughout the year. Scott Metcalfe, artistic director of Blue Heron, a Boston vocal ensemble, describes the festival as a “wonderful and long-lived institution that has done an enormous amount of interesting repertoire.”

Musicians who perform regularly with Aston Magna extol its consistently high artistic standards, the tight bonds among its performers, and its unusually wide-ranging repertory, centered on the 16th and 17th centuries but often extending backward and sometimes far forward in time.

Lovingly guiding the enterprise is Daniel Stepner, at 77 a highly respected Baroque violinist who served as concertmaster of Boston’s famed Handel and Haydn Society from 1986 through 2010. Aston Magna celebrated his 30th anniversary as artistic director (a year late because of the COVID-19 shutdown) in May with a pair of all-Schubert concerts that included the popular Trout Quintet. “I think he is slightly embarrassed by all the praise,” said David Hyun-Su Kim, a Maryland-based fortepianist who performed at the event. “There was a lot of admiration and affection for what he has given in that room.”

Though no specific date has been set for Stepner’s departure, his tenure will soon be coming to close, marking a major crossroads for the festival. It will begin having what he called “guest curators,” candidates to succeed him who will assemble and oversee some of the programs for the 2024 summer line-up and beyond. “We’re looking gradually and methodically,” he said. “The board would like a succession plan.”

After some trial concerts, Aston Magna was officially founded in 1973 — the same year as Britain’s famed Academy of Ancient Music — by harpsichordist Albert Fuller and Lee Elman, a music lover and benefactor. At the time, the Elman family owned an old Massachusetts estate called Aston Magna in Great Barrington, a town at the western end of Massachusetts in the Berkshire mountains. Lee Elman offered his palatial house for the festival’s inaugural concerts. The name stuck. (Elman’s parents, sometimes described as Berkshire cultural patriarchs, were early supporters of Tanglewood, donating money to help build what became the Koussevitsky Music Shed.)

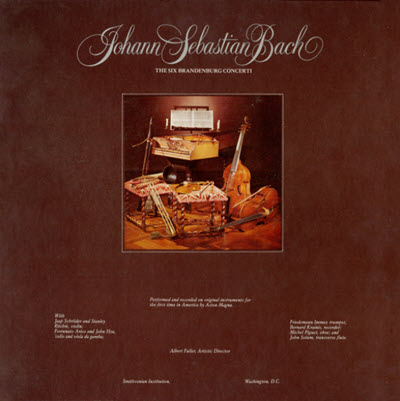

Fuller, who trained in France in the 1950s, was part of a wave of pioneering musicians across Europe and the United States who sought to rediscover the often-overlooked music of the Baroque era and before, and to rethink the romanticized, heavy-handed ways of performing it that had become the norm. In 1977, with Aston Magna, Fuller recorded the first period-instrument performances of Bach’s six Brandenburg Concertos in the U.S. In Fuller’s 2007 New York Times obituary, music critic Allan Kozinn called it “for many years a high-water mark of the early music discography. The group later had another first with its first American performances of the Mozart symphonies on period instruments.”

For its entire history, Aston Magna’s summer festival has been the mainstay of its offerings, but the festival gained considerable attention for its 13 Aston Magna Academies, held more or less every other year from 1978 through 1997 at various educational institutions, including Bard College, Douglass College, and Yale. The three-week programs, which brought together musicians and scholars in a variety of disciplines, had such titles as Music, Art, Theater, and Dance in the Age of Louis XV (c. 1725-75) and Cultural Cross-Currents: Spain and Latin America, (c. 1550-1750).

Two of the events resulted in books: Schubert’s Vienna (1997), published by Yale University Press, and The Worlds of Johann Sebastian Bach (2009). An outgrowth of the academies in the 1980s were nearly 40 “outreach academies,” smaller weekend events that took place at museums and libraires in about 30 states. “It was a fantastically heady mixture of musical and intellectual thought. It was quite exciting,” said Blue Heron’s Metcalfe, who attended a couple of the institutes. All these events were underwritten by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities and, according to Stepner, only came to end when that funding was no longer available.

‘He doesn’t sound like anyone’

Today, Aston Magna offers a summer festival with five sets of concerts (down from six at its peak), some or all performed at the Slosberg Music Center at Brandeis University in Waltham, a Boston suburb, St. James Place, a former church in Great Barrington, and in Hudson Hall in New York. In addition to a few other scattered concerts throughout the year, Stepner began a house-concert series seven years ago with each event drawing 35-40 people. “They love the intimacy of it,” he said. Audiences for the summer concerts typically number 150-175 people, said Susan Obel, the group’s executive director since 2012. “We would like to find more younger people who want to come and hear early music,” she said. “That’s a challenge.” To that end, tickets are “reasonably priced.” Children and students get in for free. Tickets for anyone younger than 30 are $15.

Rehearsals usually take place at Brandeis University, where Stepner served on the faculty from 1986 through 2006, or in his home in Newton, just outside of Boston.

Besides Stepner and Obel, the organization’s staff consists of one full-time bookkeeper and a part-time office worker, and its annual budget usually ranges from $325,000 to $400,000. “It’s small scale; it’s lean,” Obel said. The festival maintains a business office in Great Barrington, in space provided at minimal rent by a board member.

Stepner became Aston Magna’s fourth and longest-serving artistic director in 1992. Though the Wisconsin native has a national and even international reputation, he is especially esteemed in the Boston area where he has spent nearly all of his adult life. “Dan is one of our great eminences,” said Metcalfe, who as a college student studied Baroque violin privately with Stepner. “He’s done so much here and been so prominent for so many years and led so many different ensembles and contributed his really distinctive sense of programming. He doesn’t sound like anyone. He is an absolutely unique musician and one of the most curious people around in the sense that he is just omnivorous. He loves music from all different centuries.”

Initially, because Stepner had performed on both modern and Baroque violin (he was a longtime member of the modern-instrument Lydian String Quartet, which puts an emphasis on 20th- and 21st-century works) and was not as narrowly focused as earlier artistic directors, he didn’t think he was the right fit for Aston Magna. But his range proved to be exactly what drew the board to him. “I was doubtful at first myself if I was going to be the right person for the job,” he said, “but I was talked into it, and it has turned out to be a wonderful, big part of my life.”

For most of its history, Aston Magna has focused on music from the 17th and 18th centuries. “There are groups that do medieval music regularly and specialize in it,” Stepner said, “but I don’t think of Aston Magna that way. Our meat and potatoes is Baroque music and very early Classical music.” That said, Stepner has tried to broaden the group’s range by performing some earlier works but, more often, pushing into the 19th century and into the 20th century’s neo-classical repertoire — with historical performance top of mind.

Last summer, for example, in a reprisal of a program from the year before, Aston Magna presented Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du Soldat, a 1918 setting of a story of a soldier who trades his violin to the Devil. In addition to a narrator, dancer and two actors, the performance featured an ensemble of seven musicians, all performing on instruments of that period, including a piston-valve cornet and a Buffet or French-style bassoon. Stepner paired L’Histoire with another morality tale involving the Devil, Alessandro Scarlatti’s Humanita e Lucifero (Humanity and Lucifer). There was no published version of the Scarlatti, so he found a microfilmed copy of the original manuscript and created his own edition. “I’ve done it a lot, and I’ve always loved it,” Stepner said of Histoire. “I thought it was a perfect partner for the Scarlatti, which I happened upon.”

Stepner has also extensively increased Aston Magna’s catalog of recordings, with the most recent being Bach’s Art of the Fugue, which was released in 2021 on the Centaur label. He is especially proud of the group’s recordings of Monteverdi’s Orfeo (2008) and the 1707 version of Handel’s oratorio, The Triumph of Time and Truth (2006). The group has stepped outside of its usual chamber works to perform semi-staged productions of Orfeo as well as the composer’s later opera, The Coronation of Poppea — offerings that Stepner counts among the highlights of his tenure.

The group brought a presentation of the Handel oratorio to New York City in 1997 as part of a four-concert mini-tour, earning a positive review in the New York Times. “The ecology of early-music presentation is always fragile,” wrote critic Bernard Holland. “When the instruments are ‘right,’ the place is often not. Merkin Concert Hall and Aston Magna’s eight musicians and four singers, on the other hand, made a nice environmental fit on Sunday . . . The instruments, led by the strong violin playing of Daniel Stepner, filled the hall and the music in the right ways.” (Past concerts are available on the festival’s YouTube channel.)

Opportunities to Explore

Aston Magna draws on a pool of about 20 regular instrumentalists who live predominantly in the key early-music centers of New York and Boston, augmented with artists from across the country.

Julie Leven, a violinist in Boston, has performed with the group for most of Stepner’s tenure as artistic director, and she especially values the long-term relationships she has developed with her colleagues. “Those connections become more and more important,” she said. “I feel and hear it in the performances. It’s something ineffable. It’s hard to describe. But a long and positive relationship with a colleague is something I deeply value.”

She also enjoys the range of repertoire she gets to perform with Aston Magna. Leven cited, for example, a rare, period-instrument performance in July 2008 of Felix Mendelssohn’s celebrated string Octet from 1825. In a historical set-up, “the music feels and sounds different,” she said, “and as a musician who likes to explore and live with the details of what the composer might have heard, that’s really appealing.”

Fortepianist Kim, who has performed with the festival four times, agreed. In addition to Beethoven and Clara Schumann, he has performed music by Brahms on a late 19th-century Striker piano, the kind the composer preferred. For the all-Schubert celebration earlier this year, Kim played a copy of an early 19th-century Viennese piano that he owns. “Because they have such a long history, they also have an audience that is knowledgeable and receptive,” he said of Aston Magna. “I don’t think one really gets that many opportunities to do a lot of this repertoire that I’ve been talking about in a chamber-music setting. That’s not the most common thing in the world. It’s just a big treat.” (With high praise, EMA reviewed Kim’s Schumann recording last year.)

He also noted that performing these chamber works on the kind of pianos for which they were written — and not a de rigueur 9-foot Steinway D concert grand — eliminates many of the balance and textural issues associated with the latter and provide “greater sonic clarity.”

“Aston Magna is really the place where I’ve had the most opportunity to explore those things,” Kim said.

Regular performers with Aston Magna also lavish praise on Stepner, applauding both his own first-rate playing but also his treatment of fellow musicians. “He’s a wonderful colleague,” Leven said. “He is a scholar. He is humble. He thinks about everything deeply. He interprets harmonically but spins a beautiful melody on his violin that can and does make us cry.”

Tenor Frank Kelley, who lives in the southwest Boston suburb of Dedham, has known Stepner since 1983 when the two worked together at what is now known as Boston Baroque. The violinist invited Kelley to perform with the group during his first year as Aston Magna’s artistic leader, and the singer keeps coming back, drawn by the thoughtful programs, informed audiences, and the chance to keep collaborating with Stepner, whom he called a “super-accomplished musician.” Kelly served as a soloist for the Scarlatti oratorio this past summer and was narrator and stage director for L’Histoire du Soldat.

“Dan is not only musically really interesting,” said Kelley, “but he’s also very faithful to the people he has chosen to surround himself with. He’s a music director who chooses a person he enjoys making music with, and he will trust their musical capabilities and listen to what they like to do. He’s not autocratic.”

Stepner does not know what lies ahead for Aston Magna after he eventually steps down, but he is sure it will be some new direction. “I think the emphasis will always be on period instruments, whatever the period, but it may go a little later,” he said. He believes it will still be centered on 17th and 18th century music but perhaps with a different slant. “We’ll see,” he said. “I don’t know, it depends on who the director is.”

Kyle MacMillan served as the classical music critic for the Denver Post from 2000 through 2011. He is now a freelance journalist in Chicago, contributing to the Chicago Sun-Times and Modern Luxury and writing for national publications including the Wall Street Journal, Chamber Music, and Early Music America.