by Sophie Genevieve Lowe

Published June 27, 2022

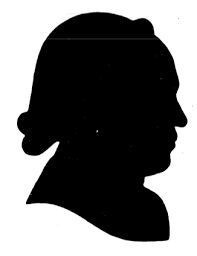

America’s first luthier, he was also likely our first composer of chamber music. The turbulent, eventful life of John Antes is a part of global histories on colonialism, revolution, international trade, nationalism, and religion. It reads like an early-music adventure novel.

Imagine the scene. The air was thick with smoldering heat in Lower Egypt on July 10, 1779. The setting sun did not quench the furnace, where for several nights the temperature lingered at 113 degrees at midnight. The city was still burying the dead who had succumbed to sudden death. Wiping his brow, a Pennsylvanian composer in Cairo began to write to a fellow American who was in France, serving as a diplomat for the nascent United States. The intent of the letter was to request that Benjamin Franklin, in the midst of trying to win French support for the American Revolution, arrange a performance of his string quartets. The composer was John Antes.

The traditional narrative of colonial America often recounts rugged individuals whose audacity, adventure, and ingenuity transcend the average experience of the public. Though the exaggerated myths of early America often do not reflect reality, there are always obscure lives whose remarkable stories go untold. From chases on the high seas, imprisonment in Egypt, and a (possible) personal connection to the great Franz Joseph Haydn, John Antes is exactly one of these obscure figures.

John Antes was born in Fredrick Township near Philadelphia on March 24, 1740. While he was still a child, the Antes family joined the Moravian community in nearby Bethlehem, setting the stage for a life rooted in the enjoyment of music. John was well educated by the Moravians, especially by his music teacher Johann Christoph Prylaeus. Moravian classical education included grounding in vocal music, with an additional emphasis for both sexes to learn instruments. The Moravians were especially known in the British Colonies for their exceptional musical standards. In 1756, Benjamin Franklin wrote that the Moravians in Bethlehem had “very fine music in the church” and that “flutes, oboes, French horns, and trumpets, accompanied the organ.”

In 1756, John Antes described having a moment of conversion to Christianity after previously doubting his Moravian upbringing. Moravians, like other Protestants, do not believe that a person is born a Christian but only becomes one through personal repentance and faith. Although Antes grew up in the Moravian community, he did not personally hold to their faith until what he described as a moment of conversion from unbelief to belief. The conversion would steer the rest of his life, and would take him from the rural countryside of Pennsylvania across the globe. After the death of his father, Antes’ brothers pressured him to leave his Christian faith. With a desire to follow his faith and be outside the influence of his family, Antes requested to be sent as a missionary by the Moravians.

While waiting to depart, Antes made his first mark on history by becoming the earliest known American luthier. Antes began by making a violin in 1759, and a viola and cello in 1763. He went on to complete two other violins, a viola, and a cello for the Bethlehem Collegium in 1764.

The 1759 Antes violin is now considered the oldest extant violin made in North America.

In a recent thrilling discovery, an Antes cello was found in the attic of a home in Pittsburgh and it is believe that this 1763 cello is the oldest extant cello built in America by an American-born maker. Visitors can see these instruments, on public display, at the Litiz Moravian Archives and Museum.

Antes’ ability to make string instruments led to the production of keyboards until this was put to a halt by the famed organ builder David Tannenberg (1728-1804), who lodged a complaint that Antes’ business was infringing on his own.

In 1764, Antes traveled to Hernnhut, Germany as he waited to be sent as a missionary. Although there are no Antes violins from his time in Germany, he appeared to have tried to make a career as a luthier. Antes bitterly remarked in a letter back to Pennsylvania that instrument makers are “the most miserable people in Germany.” In 1769, Antes accepted an invitation to serve as a missionary in Cairo, Egypt. While on the voyage, his ship was chased by Algerian pirates off the coast of Portugal.

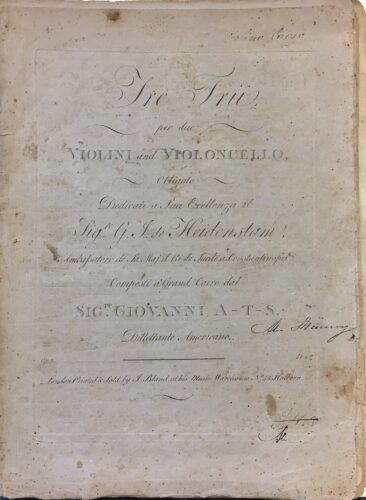

It was during his time in Egypt that Antes first made his mark as a composer. His correspondence during that time reveals references to several pieces of chamber music, of which only a set of three string trios is currently known. Notably, this work connects him to the famed London publisher John Bland, known for his publications of music by Mozart and Haydn. Bland published Antes’ trios for two violins and cello sometime before 1795. In a concoction of poor Italian and English, the title page reads as follows:

Tre trii, per due violini and violoncello, Obligato. Dedicati a Sua Excellenza il Sigre G. J. De Heidenstam, Ambassatore de Sa Maj il Ri a Suede a Constantinapel, Compasti a Grand Cairo del Sigre Giovanni A-T-S Dillettante Americano Op. 3

The title page is another Antes enigma. Billing himself as the Italianate Giovanni A-T-S Dillettante Americano, Antes dedicated the music to the Swedish ambassador in Constantinople. At first study, the anonymity of the trios seems baffling. For the Moravians, however, “all life was liturgical,” and perhaps Antes (or Bland) was finding a humorous way to publish his music without denying his conviction to humility. This semi veiled riddle kept secret the definitive authorship of the trios until 1941. The result is that this Opus 3 is the linchpin that establishes Antes as the first known American-born composer to write instrumental chamber music.

The listing of these trios as Opus 3 immediately raises the question of the possibility of two lost works. One tantalizing clue is a letter that Antes wrote to Benjamin Franklin in France during the American Revolution:

July 10, 1779

“Sir, You may perhaps still remember a young Man wich in the Year 1763 amused himself with making Musicall Instruments such as Harpsicords Violins etc. whome Curiosity and Desire of Learning once led to your House at Philadelphia, without anything to introduce him but a little American Cordiality. This Man am I… And this is the only Motive wich induce me to send you with the Pressent a Copy of six Quartetetto’s wich I have lately compossed…’”

Antes continued in his letter that he also sent his quartets to his friend, the Marquis de Hauteford, and an individual from the Harmonical Society of Bengal in Calcutta (now Kolkata) who was taking the quartets to England to be printed. The far-spanning reach of these lost quartets is staggering. Here is an American composer in Egypt sending music to Benjamin Franklin in France, a nobleman and publisher in England, and a musical society in India!

Although Antes wrote to Franklin as an acquaintance, it is interesting to note that in his lengthy letter he first and foremost approached him as a fellow American and wrote, “If I could here be of any Service to my Mother Country or to you in Particular I should allways embrace every Oppertunity with the greatest Plassure.” Years abroad had not diminished Antes’ identity as an American. Through the span of geography and history, the six quartets (presumably string quartets) that Antes sent to Franklin have regrettably been lost. The possibility of their discovery is perhaps the next chapter in the ever-materializing legacy of John Antes.

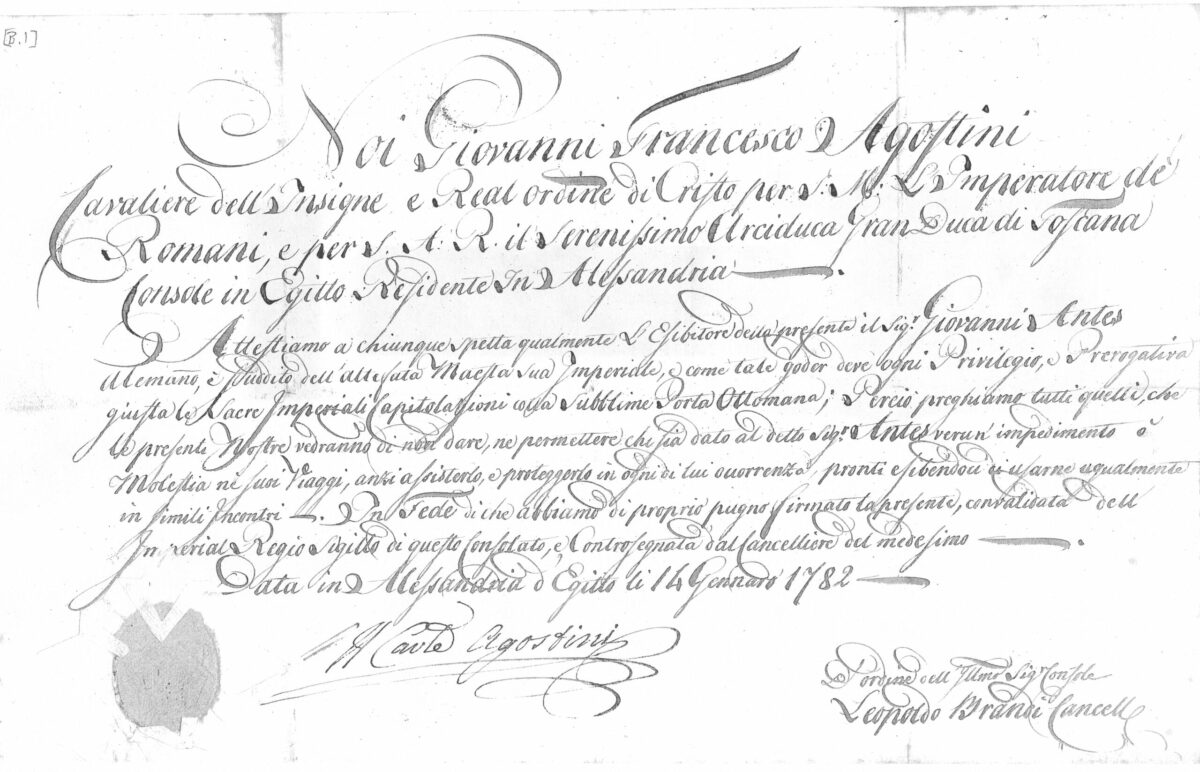

While Antes’ time in Egypt marks a period of creativity for the Moravian missionary, it did not come without risk. In 1779, followers of Osman Bey, an official of the Ottoman Empire, seized Antes and a companion. The group demanded payment and threatened to behead Antes’ companion if he did not return with gold. Horrified for his friend, Antes offered himself as a substitute hostage. He was thrown down and made to suffer bastinado (a beating of the soles of the feet that was often fatal). Antes was told the torture would only stop if he would surrender money from the church, which he refused.

He was ultimately freed when an official, whom Antes did not know, pretended Antes was a friend and demanded he be released. Because of the torture, Antes would have difficulty walking the rest of his life.

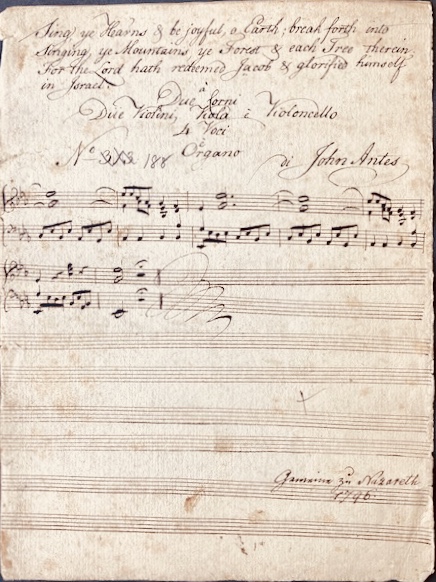

After twelve years in Egypt, Antes was recalled to Germany before eventually being sent on to England. Sometime between 1781 and 1785, Antes began a second period of compositional inspiration, now focused on sacred music. During this time, Antes wrote at least 59 chorale melodies and 31 anthems. One of his anthems of 1796, “Now May the God of All Grace,” again reveals Antes’ affection for his native land, the music being composed for the Moravians in Pennsylvania.

Perhaps in conformity with British and European practices, Antes’ chorale works are composed for SATB, departing from the typical Moravian SSAB setting. His choral music is characterized by long vocal lines with a soaring tessitura, dotted rhythms, and often by ingeniously constructed string accompaniments that reveal the amateur composer’s contrapuntal prowess. It is probable that Antes played his violin parts with his congregation while in England. In a typical irony of Antes’ musical life, although the majority of his anthems were composed while he was in England, they were preserved in the United States after being copied by a musician in the service of America’s Moravian congregations, Johann Friedrich Peter (1746-1813).

One of the most tantalizing mysteries of Antes’ life comes from his time in England, where he may have been an acquaintance of Joseph Haydn. There are various ways Antes could have made the connection. For example, Antes recounted that the great violinist and impresario Johann Salomon (1745-1815) was a friend, and had admired Antes’ invention to improve the violin bow. Salomon, in cooperation with publisher John Bland, worked together to secure Haydn’s passage to England. Salomon humorously had told Haydn, “I am Salomon from London and I have come to fetch you.” Did Antes’ friend and publisher ever introduce him to Haydn?

Another possible connection comes through Antes’ nephew, clarinetist Christian Latrobe (1758-1836), who was Haydn’s close acquaintance. It does not seem a stretch that Latrobe would introduce his uncle to his friend while they were all in London. In fact, in Haydn’s first London notebook of 1791–1792, Haydn indicates a “Mr. Antis, bishop and minor prophet.” Though there isn’t yet any evidence to back up the claim, some scholars have suggested that Haydn and Antes played chamber music together. Musically, it is irresistible not to compare Haydn and Antes to some degree. The Moravians were using Haydn’s published music as early as 1765, so it is highly probable that Antes would have been familiar with the master’s work as a student in Bethlehem. Whether or not they shared a music stand is yet another enticing riddle of Antes’ life.

Still suffering from his torture in Egypt, Antes retired to Bristol, England. In 1811 Antes died cheerfully, looking forward to the fulfillment of his faith, “then how joyful shall I sing.” The musical legacy of John Antes is nuanced and complicated. Although he is a much-beloved composer of the Moravians, his compositions, most especially his string trios, do not make it to the concert hall. In addition to their historical significance, the string trios are dazzling and do merit modern performance. The advancement of scholarship into John Antes opens up the possibility of finding more missing instruments and the lost quartets. It is with hope that, in sharing this article, EMA’s community of artists, scholars, and music lovers will come to find similar enjoyment and appreciation for the works and lives of Antes, and the multitude of other music makers who lived and worked in vast Early America.

Sophie Genevieve Lowe is a Baroque violinist and graduate of the Royal Academy of Music, London. In addition to performing, she is an avid researcher of music from Colonial America.

This article is the first in a series. Early Music: the Americas is presented by EMA’s Emerging Professional Leadership Council.

Others in the series: