by Karen M. Cook

Published August 5, 2024

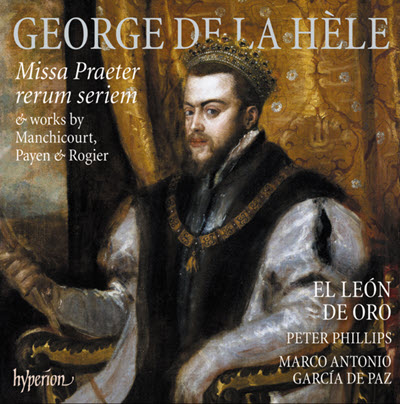

George de la Hèle: Missa Praeter rerum serium & works by Manchicourt, Payen & Rogier. El León de Oro, conducted by Peter Phillips and Marco Antonio García de Paz. Hyperion CDA68439

Until his death in 1598, Philip II reigned as Duke of Milan from 1540, as Lord over the Hapsburg Netherlands from 1555, and as King over Naples and Sicily from 1554, Spain from 1556, and Portugal from 1580; by dint of marriage, he was also King of England and Ireland from 1554–58. It is no wonder that his reign oversaw Spain’s “Golden Age,” for such an illustrious set of credentials warranted an equally illustrious court — and, since he was faced with upholding Catholicism in the faces of both the Protestant Reformation and the expanding Turkish Empire under Suleiman the Magnificent, an equally illustrious chapel.

In Philip II’s royal court there were two primary musical groups: the Capilla Real, made up of Spanish instrumentalists, and the Capilla Flamenca, largely composed of Flemish singers. The interest in what many might call Franco-Flemish polyphony began in the reign of Philip’s father, Charles V, who was himself both King of Spain and Duke of Burgundy. In fact, Charles’s last maestro de capilla (and Philip’s first) was the Fleming Nicolas Payen.

On this latest album from Spanish ensemble El León de Oro, conductor Marco Antonio García de Paz and guest conductor Peter Phillips (founder of the Tallis Scholars) take an aural tour through Philip’s reign. The album features works by Payen and four of his subsequent maestros, Pierre de Manchicourt, George de la Hèle, and Philippe Rogier.

Of these, Manchicourt is perhaps the most familiar, although he is hardly a household name, while de la Hèle and Payen are largely unknown today. This is certainly not due to any flaw in their musicality, as this album aptly demonstrates; unfortunately, this repertory has been hard hit by natural disasters in subsequent centuries. Rather than organizing the material chronologically, as one might expect of such a tour, the material is organized primarily by conductor. The album starts off with the world premiere of de la Hèle’s hefty Missa Praeter rerum serium, conducted by Phillips. One of numerous masses to parody Josquin’s motet, de la Hèle adds a seventh and later an eighth voice.

The second half of the album shifts to the motet genre and to the other composers: Phillips again takes the lead on two of Manchicourt’s motets, while García de Paz takes over for Manchicourt’s Regina Caeli and the Payen Virgo prudentissima, and each composer gets a turn with Rogier.

It’s a larger ensemble, with over thirty singers, but there is no wall-of-sound effect here. All of the different voice parts come through well and with a nice sense of precision. The Mass alone makes the album a worthwhile listen; the Amen at the end of the Credo is particularly effective, the higher range of the Benedictus is a beautiful counterpoint to the largely darker sonorities that pervade both the original motet and this work, and the slower imitative build to the Agnus Dei is quite striking.

The Manchicourt settings are, as Phillips observes in the liner notes, the kind of polyphony that needs to unwind. The opening statement from the highest voices in Osculetur me is sinuous and inviting, while the joyful tone and shorter length of his Regina Caeli create a sense of faster, more buoyant motion. The Payen layers sustained melodies over the more active lower voices, while the familiar opening motif of the chant seems to shift ever downward. The Rogier motets are quite a change in style and tone: Cantantibus organis is jubilant, bright, and homophonic, while his own Regina caeli showcases the burgeoning double-choir style, with its contrasting tempi and meters. An exciting and educational listen.

Karen M. Cook is Associate Professor of Music History at the University of Hartford. She specializes in late medieval music theory and notation, focusing on developments in rhythmic duration. She also maintains a primary interest in musical medievalism in contemporary media, particularly video games. For EMA, she recently reviewed the Fieri Consort singing of the Excellence of Women: Casulana and Strozzi.