by Pierre Ruhe

Published February 7, 2022

Who’s in charge? Who plans the programs, hires the performers, raises the money and then decides how and where and by whom it will be spent? More specifically, who has control? The Gatekeeper. It’s the typical term for administrators who run an organization—in non-profits, academia, business—often used by people who are outside looking in.

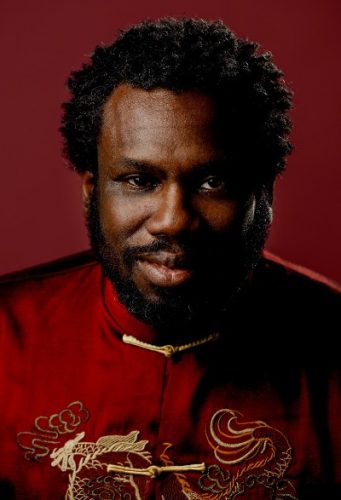

The Open Gates Project is a recent initiative to start from the opposite direction, to throw open the gates of early music and historically informed performance. Hosted by Gotham Early Music Scene (GEMS) and led by two singers, Joe Damon Chappel and Michele Kennedy, the project is being built from the ground up.

They boil it down to a blunt, personal question. Until recently, it was almost never part of any gatekeepers’ discussion: How many times has an artist of color entered a rehearsal room full of musicians only to discover that they are the only artist of color—although they know many capable colleagues of color who weren’t asked to participate?

“We talk about it,” says Kennedy, a soprano, “how often we’re the only person of color in a group, so there’s a lot of ‘othering’ and you feel you’re on your own.”

Open Gates, she says, addresses the problem from a positive perspective. “It comes from a place of affirmation, of joy and mourning and celebration, suffering and most of all listening. We love the early-music repertoire and the end result, always, is to put on a great concert, a meaningful concert.”

To that end, Open Gates’ inaugural season continues with its second performance, this Friday (February 11) in New York, a concert called C3: Countertenors, a Consort, and Continuo. Once they were into the planning stages, Chappel and Kennedy found a shared interest to explore and celebrate unique combinations of sound and timbres. Music by Byrd, Purcell, Handel, and other Baroque composers are on the bill, along with something new.

By necessity, as much financial as artistic, Chappel thinks of early music as one component of a career, along with wet-ink new music—in both cases you’re not so much repeating ingrained traditions as searching for a sound that’s true to the composer. So the C3 program includes a work by Trevor Weston who, among his many commissions, works with Black church choirs in New York and also the classical avant-garde in Paris. Weston composed O Maria for countertenor and viols, although for logistical reasons in the new-music scene, it was never performed that way. This week’s concert will be its original scoring premiere.

“We were interested to rediscover and showcase forgotten voices,” says Chappel, a bass-baritone, “voices and instruments and people that had fallen out of favor or have not been given an opportunity”—including men of color, the countertenor voice, and instruments like viols that are central to the early-music community but exotic and bewildering to almost everyone else. “Symbolically it represents marginalized voices that most people, inside and outside concerts, don’t think of.”

Appealing to audiences beyond the expected early-music crowd is key. “Outreach is the mission, where we take early music to places it hasn’t gone before,” says Chappel. “That means performing in a usual GEMS venue”—a church in Manhattan, for example—“but also in the Bronx and Jamaica, Queens. Give out lots of student comp tickets, entice people who don’t know anything about early music to come and experience it. We’re building up the audience from there, with fundraising and grants to follow.” Chappel knows they have their work cut out for themselves. Gatekeepers, in any field, are sometimes the mere fonctionnaire following orders, like Caronte, the cranky boatman on the River Styx from L’Orfeo. Just as often, restricted access comes from ambitious leaders who can successfully (and consistently) tap a variety of funding sources, often keeping it within a network of patronage. Compelling art and noble outreach grabs our attention and keeps us engaged, but behind the scenes someone has to deliver the money. Money is the surest way to buy control.

Speaking ‘The Truth’

Kennedy talks about propping open the door for other early-music performers of color to follow. “What does it mean for me as an artist?” she asks. “The idea for Open Gates was this: How can I use my voice”—in all senses of the word—“to leave a mark beyond my last performance?”

There’s a phrase Chappel uses a lot: Representation matters. He tells the story about one day at school, when the music teacher presented various stringed instruments to the students. “If a young kid sees someone up there who looks like them, who looks like me, showing them something wonderful and making it seem entirely natural, that says there’s room for me in that world.”

Viol player Patricia Ann Neely has been outspoken about representation in early music, and she comes to it as both a supporter of the field—she’s a member of the EMA Board of Directors—and also as a performer.

“Often I’m the only Black instrumentalist in a group,” Neely says, “and I can’t hide how I look. We have to make sure the community can see themselves on stage to feel comfortable. No one is going to get into playing the viol on their own, without seeing people like themselves as instrumentalists.”

“It’s a slow process,” she admits. “I really applaud GEMS for taking on Open Gates. It’s one thing to issue a statement, another to do the hard work and present concerts.”

By design, this week’s C3 concert is “a twin” to the Open Gates’ debut performance, in November, 2021, The Divine Feminine: Centering Women of Color in Early Music. That first concert surpassed expectations, Chappel notes, although our endless global health crisis has, of course, impacted everything.

Open Gates’ mission has three compelling points, called “truths.” For its persuasive language and sharp observations, the statement is worth quoting in full:

- Artists of color deserve equity in representation on the stages of Early Music performance; indeed, they are entitled to equity in access and the creation of safe, supportive, non-discriminatory spaces for nurturing and displaying their artistry. They are not visitors in their own craft – but fully vested practitioners, stewards, and teachers of their vocation and should be regarded as such.

- Communities of color deserve open access to the performing arts – all of them and in all styles, including Early Music. Early Music does not belong to anyone if not to everyone. No matter our ancestral path, as citizens of Western Civilization, people of color are entitled to claim the cultural heritage and legacy of Early Music as their own, because it is. They have bought and paid for it in the tumultuous history of colonization, forced cultural replacement and appropriation, and globalization. People of color needn’t constantly prove their right to enjoy Early Music. Their appreciation is as valid as anyone else’s.

- Until audiences see themselves reflected on the stage, they will always feel like outsiders when they absolutely should not. Early Music is glorious, transformative, and wonderfully and ironically relevant to the modern aesthetic. Above all, Early Music belongs to us all.

As Kennedy puts it, “We want folks of color to feel a sense of belonging at our early-music concerts. For us, we know that the work of inclusion is a hard and daily effort. That’s the heart of the Open Gates Project. How can we open the door to other artists who didn’t have that door open when they were coming up?”

Pierre Ruhe is Publications Director of Early Music America. He can be reached at editor@earlymusicamerica.org