by

Published March 16, 2018

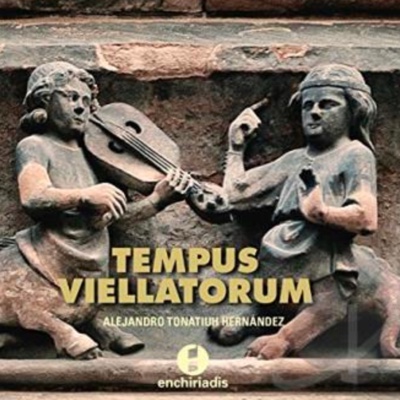

Tempus Viellatorum: Fiddle in the Music of the XIII Century

Alejandro Tonatiuh Hernández

Enchiriadis EN2047

By Karen Cook

CD REVIEW — Few instruments in medieval Europe were as important, or perhaps as prevalent, as the vielle. Along with the harp and other plucked stringed instruments, it was linked to both amateur and professional musicians of all social statuses who used it to play dance music, perform, or accompany a variety of secular songs, and even to accompany sacred music.

The vielle is documented in all sorts of manners, from sculptures to paintings and illuminations, from descriptions in literature and poetry to discussions in theoretical texts. Two late 13th-century theory treatises provide us with considerable information. Jerome (Hieronymus) of Moravia’s Tractatus de Musica (c.1280) concludes with a section on bowed strings and an overview of the various tuning systems used for the vielle. Since the treatise is geared toward fellow Dominican friars, it seems that the vielle might have been used in a church setting as well as in secular society. Just a few decades later, the theorist Johannes de Grocheio also writes about the vielle in his De Musica. Rather than discussing tuning and construction, Johannes talks about repertoire. For him, the vielle was the most important instrument, as it was capable of performing all genres of music both monophonic and polyphonic, which he then describes in great detail.

The vielle is documented in all sorts of manners, from sculptures to paintings and illuminations, from descriptions in literature and poetry to discussions in theoretical texts. Two late 13th-century theory treatises provide us with considerable information. Jerome (Hieronymus) of Moravia’s Tractatus de Musica (c.1280) concludes with a section on bowed strings and an overview of the various tuning systems used for the vielle. Since the treatise is geared toward fellow Dominican friars, it seems that the vielle might have been used in a church setting as well as in secular society. Just a few decades later, the theorist Johannes de Grocheio also writes about the vielle in his De Musica. Rather than discussing tuning and construction, Johannes talks about repertoire. For him, the vielle was the most important instrument, as it was capable of performing all genres of music both monophonic and polyphonic, which he then describes in great detail.

On this new recording, Alejandro Tonatiuh Hernández plumbs the depths of Jerome’s and Johannes’s treatises to find out how the medieval fiddle would have been played, how it would have sounded, and how it would have been used. The Mexican-born Hernández uses two of the tuning systems mentioned by Jerome; both involve a separate string called the bourdon that acted as a drone, with the rest of the strings tuned in fifths and octaves from there. Since Jerome indicates that the bourdon could be either plucked with the thumb or bowed, Hernández uses both approaches here.

On most of the works he plays alone, the flatter bridge of the vielle and the added bourdon string allow him to embellish a monophonic melody either with a drone or with an actual countermelody, as Jerome discusses. On other selections, however, he brings in a citole (a small plucked string instrument), a muse (a precursor to the bagpipe), and a variety of percussion instruments. As for the repertoire, Hernández identified works mentioned specifically by Johannes and other similar pieces. Since the vielle was used in so many different contexts, the material runs the gamut from troubadour or trouvère songs (such as Adam de la Halle’s Merveille est quel talent j’ai de chanter) to sacred conductus settings (like Florex fex favellea or O varium Fortune, from the Roman de Fauvel manuscript Paris B. N., fr.146) to instrumental estampies from the Manuscrit du Roi.

The different types of instrumentation, and Hernández’s varied performance tactics in rendering these polyphonic (or embellished monophonic) pieces on the vielle, bring new life to this repertoire, especially the conductus, which I tend to hear more frequently performed as vocal works. It’s an engaging sound world, and a thoughtful, thought-provoking approach to both the instrument and its likely repertoire.

Karen Cook specializes in the music, theory, and notation of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods. She is assistant professor of music at the University of Hartford in Connecticut.