by Dominic Giardino

Published July 25, 2022

Timothy Olmsted lived a life with music at its center. Through wars and nation-building peace, he cultivated an eclectic career as a fifer, bandleader, and chorister, all the while composing and arranging his own music. He was, as one writer later put it, “music mad.” Then as now, however, a freelance musician’s biggest struggle often isn’t their craft, but putting food on the table.

Early Life, 1759–1774

After nearly one hundred years of sustained conflict, spanning five wars between Great Britain, France, and Indigenous peoples of North America, the year 1759 closed with a hint that lasting peace could be on the horizon. British victories in upstate New York and Quebec created an untenable situation for France as an American colonial power. Britain’s decisive wins in North America, combined with further victories in Europe, the Caribbean, and Asia, led to 1759 being dubbed an annus mirabilis, or miraculous year. Celebrations were held throughout the burgeoning empire:

“BOSTON, October 15 – We hear that the… Chaplain to his Excellency the Governor… is to preach a Sermon To morrow… on Occasion of the Success of his Majesty’s Arms in the Reduction of Quebec. After Divine Service is over, his Excellency and the Court are to dine together at Fanueil Hall, and in the Beginning of the Evening are to be entertained with a Concert of Music at Concert Hall… The Joy on this Occasion is the most sincere and universal…” – Reprinted in The Maryland Gazette, Annapolis, Maryland, November 1, 1759

It was into this optimistic British America that Timothy Olmsted was born on November 14 in East Hartford, Connecticut Colony, the sixth child of Mary and James Olmsted.

Like the majority of colonists in Connecticut, Timothy was raised as a Congregationalist. Consequently, it seems very likely that he and his siblings would have been educated in reading music during their youths. By the time Olmsted was a toddler, the inter-Congregationalist dispute over singing in the “Old Way” versus singing “By Rule” (i.e. from notation) had tipped heavily in favor of the latter, effectively institutionalizing music literacy across the colony. Even so, Olmsted’s career suggests that his musical upbringing wasn’t restricted to the church.

Also like many New Englanders, Olmsted’s family had served alongside British soldiers in the various American wars against the French. Records suggest that his father was one of the estimated 16,000 men to join Connecticut’s provincial regiments during the French and Indian War (1754–1763). A document from 1758, however, indicates that James Olmsted was “Released by the Colonel of the standing Militia,” and consequently was exempt from duty.

Growing Up Quick, 1775–1776

Any positive feelings that were still lingering from the annus mirabilis were replaced with anxiety by 1775. Throughout Olmsted’s formative years, the metropole’s efforts to centralize parliamentary authority over the colonies sparked discontent from the Caribbean to Canada. Tensions were greatest in New England, where political dissidents became increasingly brazen in their opposition of British policy. By 1774, the city of Boston was effectively under British military occupation. In response, newspapers throughout the colonies printed statements of solidarity that laid the foundation of a united front:

“[The Policies] relating to the Town of Boston in Blocking up their Harbour, and the Province of the Massachusetts-Bay in mutilating their Charter, and stripping them of their most valuable Privileges… and the most essential Liberties of the English Constitution—-and a Military Force, ordered by the Crown to awe them into a Submission to the same… These Measures… give the most clear and formidable Proof that the Court and Parliament of Great-Britain design to have the Government of the Colonies intirely in their own Hands… we ought to exert ourselves with the greatest Firmness, Union and Resolution, to avoid the Oppression that threatens us.” – Proceedings of the Town of East Windsor, moderated by Erastus Wolcott, printed in the Hartford Courant, Hartford, Connecticut, August 23, 1774

Seemingly overnight, the notion of a peaceful reconciliation between Britain and thirteen of her colonies went from the expected resolution of the “Imperial Crisis” to a delusion. There would be no lasting peace in North America.

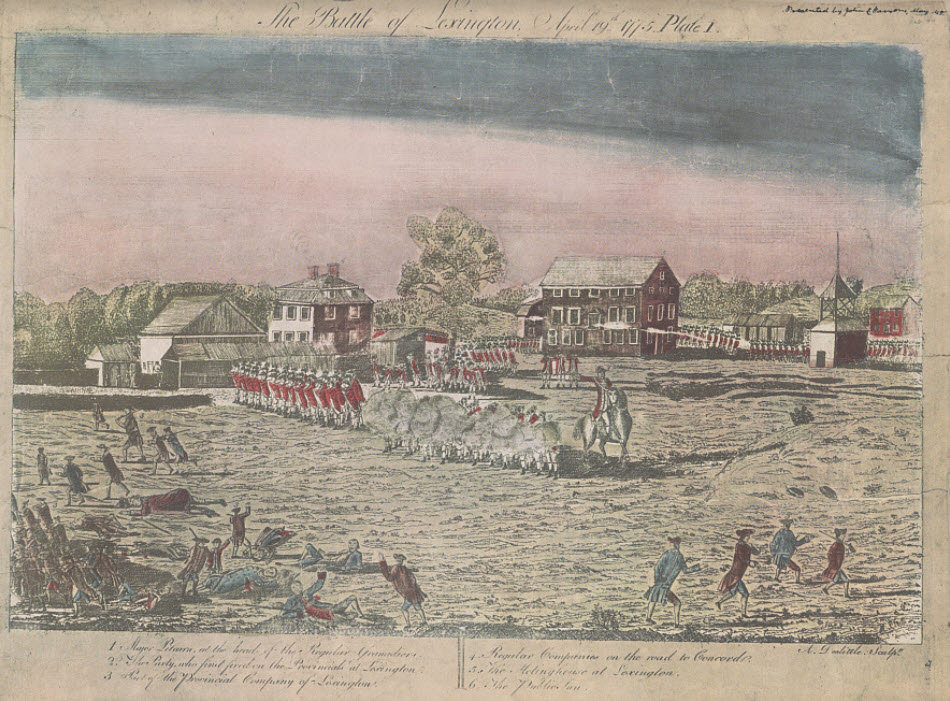

On the morning of April 19, 1775, the first shots of war between British soldiers and Massachusetts militiamen were exchanged at the small town of Lexington, less than 100 miles from the then 15-year-old Olmsted. Circular letters from Massachusetts were dispatched immediately, and the adolescent was 1 of 143 from Hartford to answer the Lexington alarm. It is on this first muster roll that Olmsted is introduced to us as a musician, “Timothy Olmsted,… Fifer.”

The origins of Olmsted as a fifer are entirely unknown. By 1773, flutes, fifes, and even “Instruction Book[s] for Flute, Fife, Violin, &c.” were all available to purchase at Hezekiah Merrill’s apothecary and bookstore in Hartford, giving him a potential source for an instrument and route for self education. It is equally plausible, given Connecticut’s long-established military traditions by this time, that Olmsted could have been taught by another fifer in the militia preceding the war. Regardless of how Olmsted ultimately took up the instrument, it is clear from the sources that his talents were recognized early.

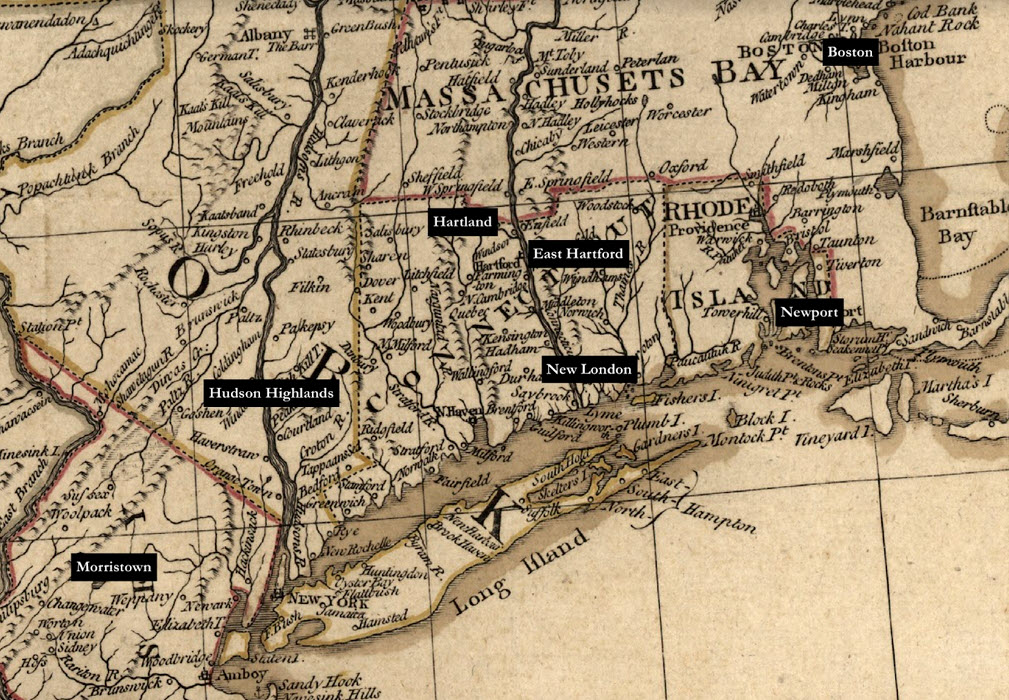

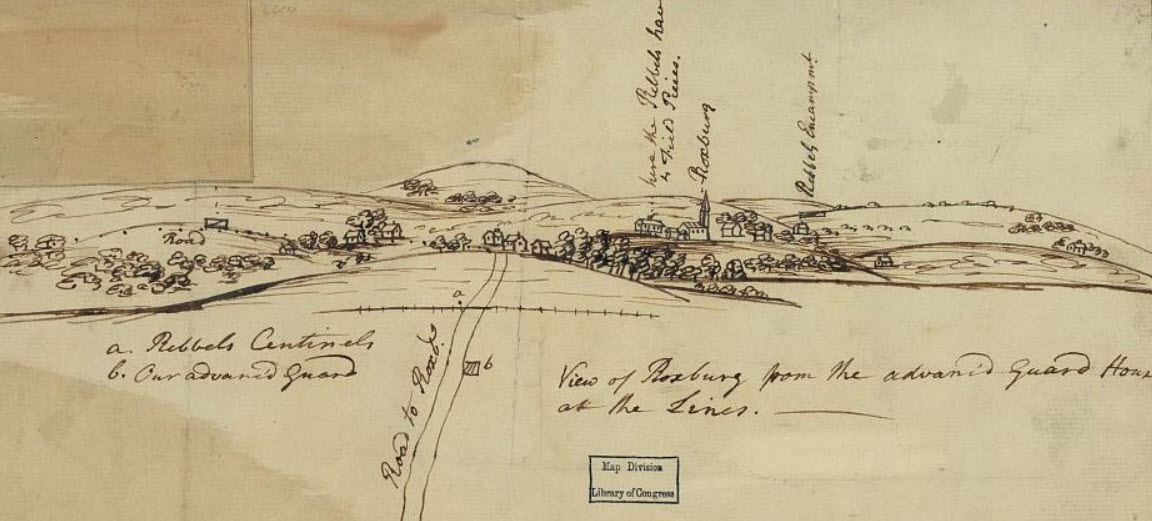

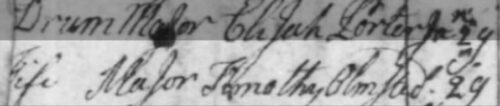

After a short six days of service following the Lexington alarm, Olmsted enlisted as a fifer in Col. Samuel Holden Parson’s Regiment and was bound for Boston, where the British Army was quickly coming under siege. After arriving at Roxbury in June, Olmsted’s regiment was “employed in building Forts and breastworks all along the shore.” The siege of Boston was still underway when his enlistment ended on December 17, and in January 1776 he reenlisted in Colonel Erastus Wolcott’s Regiment. In a significant testament of Olmsted’s abilities, the 16-year-old was appointed as the regiment’s fife major. Promotion to this senior musical rank meant instructing and managing the regiment’s eight other fifers.

By the mid-18th century, the British infantry had largely done away with fifers, and the duties of signaling in garrison, camp, and on the battlefield were predominantly carried out by drummers. The Continental Army, on the other hand, relied on both fifers and drummers together to fulfill these responsibilities.

Throughout 1775 and 1776, Olmsted’s fife would wake his comrades every morning, let them know when it was “lights out” in the evening, and call them to meals and duty in between. Almost everything a soldier did in the Continental Army was initiated by the tunes and beatings of fifers and drummers, and it was critical that fife and drum majors adequately instructed their subordinates to perform stoically in the face of cannonades and musketry.

Following the British evacuation of Boston, Olmsted was once again discharged from service in April 1776. At this point, he drops out of the records until May 1777, leaving his whereabouts during the critical campaign season of 1776 a mystery. Today we recognize 1776 as a celebratory year of independence, but the situation on the ground could not have been more precarious. In August, a British army 32,000 strong launched a strike on New York City that left Manhattan occupied until 1783 and sent General George Washington’s Continental Army on a retreat for its survival. Earlier victories for the Americans in Massachusetts were quickly being overshadowed by devastating defeats in New York and Canada.

Recognizing the need for more troops in the field, on December 27, 1776, the Continental Congress authorized that:

“General Washington shall be, and he is hereby, vested with full, ample and complete powers to raise and collect together in the most speedy and effectual manner, from any or all these United States, sixteen battalions of infantry in addition to those already voted by Congress, [and] to appoint officers for the said battalions…”

It is in one of these so-called “additional regiments” that Olmsted once again appears in the sources.

Master of the Band, 1777–1780

Recruitment was slow to start during the early months of 1777, but that didn’t stop the newly commissioned Col. Samuel Blachley Webb from devising extravagant plans for his first command. The ambitious 24-year-old Connecticut native had already distinguished himself as a soldier at the battles of Bunker Hill (June 17, 1775), White Plains (October 28, 1776), and Trenton (December 25, 1776), and as an aide-de-camp to both Generals Israel Putnam and George Washington. This new responsibility was the logical next step in a promising military career, and Webb was determined to make his new “additional regiment” as impressive as possible.

The organization of the Continental Army was, in most ways, based on the British system, but Webb took this modeling to the next level. At its inception, Webb’s regiment had nine total companies, of which one was designated as the grenadier company (the “assault troops”) and another as the light infantry company (the “skirmishers”). They were clothed in captured British uniforms, being referred to as “Webb’s Regiment of Red Coats,” and the officers supported a band of music, an ensemble that was entirely separate from the regiment’s fifers and drummers. Olmsted would serve as “the Master of the Band” from May 1, 1777 until May 1, 1780, and as such would be responsible for rehearsing and instructing the musicians and procuring music.

Military bands in the Continental Army were particularly rare. Unlike the “field music” (fifes and drums), bands of music were funded by officers and exclusively meant to entertain. Despite the physical, material, and financial challenges of war, however, Olmsted and his fellow musicians were recruited specifically for the band. The group’s story and financial circumstances are concisely packaged by Prosper Hosmer, a fellow bandsman, in his pension application:

“In the Spring of 1777 we… met in Hartford in order to Prattis as a band of musick to l’aine Col. Webbs Regiment and the officers of said Regiment promis’d to add five Dollars to our pay making us Ten Dollars a month which promis they fullfild untill may 1780 and the Band then was Broken up as 5 of the Band was for 3 years and they would not relist againe… The Five Dollars aded to our pay was to help us in our Cloathing and keep ourselfs neat & Clean ready to be Call’d on before Company to play…”

To get the band started, Webb paid £58.11.0 to Solomon Ballentine in Hartford “for the Music.”

Historian Ruth Mack Wilson notes that the £58.11.0 paid “would have been enough for both music and instruments for the standard Harmoniemusik combination of two each of clarinets, oboes, French horns, and bassoons.” Bands of music could, however, consist of any combination of wind instruments, minimally combining two clarinets or oboes, with two horns to reinforce harmony, and a bassoon in the bass. While it’s safe to consider that the band sported the “standard Harmoniemusik combination,” the only information we have about the ensemble’s instrumentation comes from the pension of another bandsman who “played on a clarinet during the time.”

Though Webb’s Regiment was ordered to rendezvous with the army at Peekskill, New York, as early as April 1777, slow recruitment kept Webb in Connecticut until early July. It’s very likely that the band was on recruiting duty during this time, and in that capacity would have witnessed another peculiarity of Webb’s regiment. Despite early efforts in 1775 by General Washington to prohibit Black men from joining the Continental Army, he was ultimately pressured to concede, and the army remained largely integrated throughout the conflict. Webb, however, specifically denied Black men from joining his regiment, despite his shortage of recruits. He even wrote to Washington in June of 1777 seeking approval for this policy of discrimination, “I hope my conduct in refusing them (though many have applied) will be approved of.”

The band of young musicians (the oldest was William Hooker at about age 20, and the youngest was Epaphras Jones, who was only 14 years old) spent the summer of 1777 in the Hudson Highlands. Though a force of 7,000 hostile soldiers was garrisoned less than 50 miles down the Hudson River, the summer was relatively uneventful. In August, Webb’s regiment took part in a brief excursion back to Connecticut for an unsuccessful raid on Setauket, Long Island, but was back on the Hudson River by late September.

Due to an intensifying situation in upstate New York, October would bring Olmsted within mere miles of the enemy. Early in the month, 2,000 British soldiers were dispatched from Manhattan to reinforce General Burgoyne’s army at Saratoga, New York. These reinforcements ultimately were unable to reach their objective, but the raids they conducted along the Hudson destabilized the region throughout the month. Tense as this period was, though, the first mention of the band performing appears in Webb’s journal two days before the British withdrew back to Manhattan:

“Hurly [NY], Fryday, 24th. Octor., 1777. His Excellency the Governeur gone over the River, orders for us to be in readiness to march on the shortest notice; spent the day riding, the Evening the Miss TenEycks & Miss Betsy Elmondorph — with several Gentlemen — were at my quarters — pass’d it sociable with the Band of Music &c — &c.”

Between October 24 and December 4, the band is specifically mentioned three more times in Webb’s journal referencing: an “Evening spent with decent sociability in Company with my Officers,” an “Evening [where] a Number of Ladies alias Women [came] to hear the Band,” and an “elegant Dinner provided at Doctr. Hills about Twenty officers present.” The band was fulfilling Webb’s social expectations, and Olmsted was apparently impressing.

Webb, his regiment, and the band were all back in Connecticut in December 1777 in anticipation of another surprise raid on Setauket. Bad weather threatened to cancel the operation, but eventually the raiding party was given the green light on December 10. Disastrous results would follow. Webb’s boat was spotted by a British ship as it crossed the Long Island Sound, and he was forced to surrender. He would spend the next several years away from his regiment as a prisoner of war.

Unfortunately, the sources tracking the band during Webb’s absence are lacking. We know that the band continues until May 1780, and later pension records corroborate the band’s various movements with Webb’s Regiment:

“… halted at West Point the winter of 1777 and 1778 where [we] built Fort Webb – In the year 1778 moved to Rhode Island, were at Providence – Bristol – Warren… wintered 1778 & 1779 in barracks at Tiverton Massachusetts – after the British evacuated the island of Rhode Island we took possession of Newport Rhode Island crossed from thence to Greenwich continued on our march through Connecticut by way of Hartford to Verplanks point on the North river N. Y. Crossed to Stony Point thence to Hackensac New Jersey proceded on our march to Morristown New Jersey where we tented until January then hutted through the winter of 1779 and 1780.”

By 1780, the Continental Army was tired. Underpaid, under-equipped, under-fed, and under-clothed soldiers weathered the emotional and physical brutalities of a conflict with no end in sight. Though 1778 saw the French enter the war on the side of American independence, Olmsted and the band witnessed the disastrous first attempt at Franco-American cooperation during the siege of Newport, a failed operation that left both allies understandably unimpressed with each other. As patience and patriotism wore thin, the brutal winter of 1779–1780 was the last straw for many.

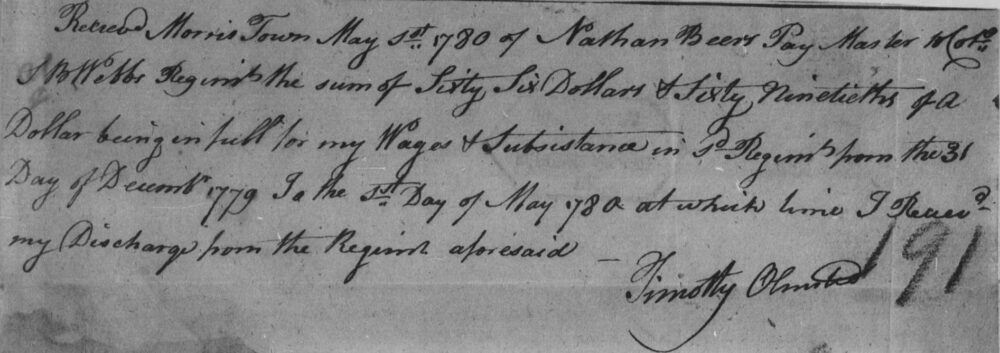

Attempts were made to keep the musicians together, however, Lt. Col. Ebenezer Huntington wrote to Webb on February 16, 1780 with a postscript asserting that “Money nor promises will reenlist the band.” In May, Olmsted and four other members of the ensemble were discharged at Morristown, NJ. The remaining three were left to complete their enlistments. A year and a half later, in October of 1781, the combined Franco-American army under the Comte de Rochambeau and General Washington forced General Cornwallis into capitulation at Yorktown. Stephen Moulton, Olmsted’s aforementioned clarinetist, would be there to see the surrender that turned the world upside down. Peace was finally in reach.

Finding a Voice in the Early Republic, 1782–1811

While we can assume that Olmsted traveled immediately back to Hartford following his discharge in May 1780, he once again falls out of the records until 1782. In May of that year he married Alice Olmsted, his second cousin, with whom he had thirteen children. Later, on October 10, he was appointed assistant chorister in East Hartford First Society. From 1782 until at least the 1810s, he worked consistently as a music teacher, composer, and church musician in various capacities.

In 1785, he moved to Hartland, Conn., where he added farming and horse breeding to his professional portfolio. At some point in this period, Olmsted and fellow New England-born composer Andrew Law became acquainted. While Law wasn’t always known for playing friendly with other musicians, several of Olmsted’s compositions appear throughout the 1790s as a part of Law’s published collections of sacred music. Clearly there was some level of respect between the two, and it has been suggested that Olmsted was Law’s student. Sources to confirm such a relationship, however, have yet to be found.

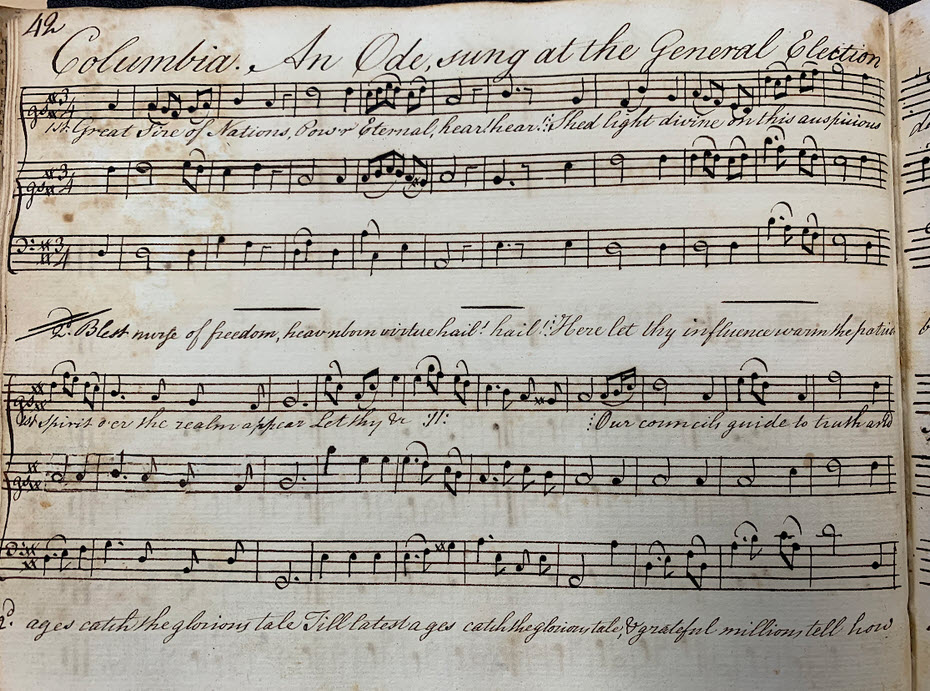

Despite Olmsted’s total absence from print advertising in the latter two decades of the 18th century, there are hints that suggest his music was enjoyed throughout the state during this time. Housed at the Connecticut Historical Society (CHS) is a manuscript music book containing “Columbia, an ode sung at the general election in Hartford, 1792” composed by Olmsted. The civic theme and purpose of this work demonstrates Olmsted’s early musical participation in the young republic’s public sphere.

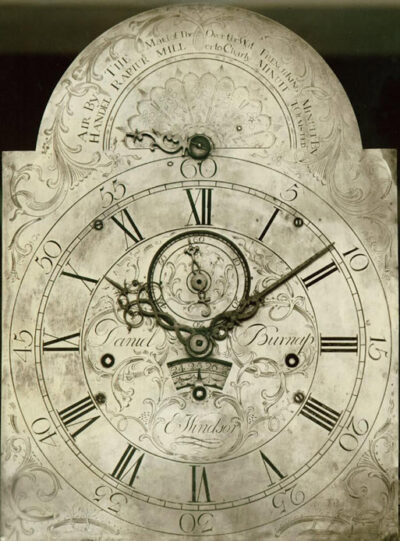

An even more curious piece in CHS’ collections is, however, a musical tall clock built sometime between 1785 and 1800 by Daniel Burnap of East Windsor, Conn. Operated through a series of weights, metal scrolls, bells, and a dial on the clock’s face, the clock is able to play six tunes: Air By Handel, The Rapier, Maid of the Mill, Over the Water to Charley, French King’s Minuit, and Minuit by T. Olmsted. In this largely pre-industrial era, where novelties like metal scrolls for musical clocks had to be made meticulously by hand, the inclusion of Olmsted’s Minuit can be understood as nothing less than fandom.

Olmsted was a devoted teacher and, according to a later biographical sketch, “music mad.” A student of his provides us with some insight in a letter written to Andrew Law in 1804:

“He has been with us about 3 weeks teaching psalmody. He devotes 6 afternoons and evenings each Week in instructing. His forenoons are employed in completing a manuscript volume which he has been composing & collecting some time past for publication…”

Talent and business acumen, however, can often be at odds. The same letter quoted above goes on to say that, “In his worldly affairs he has met many losses & disappointments, & hopes by his tas[t]e & industry to acquire some money by his books.”

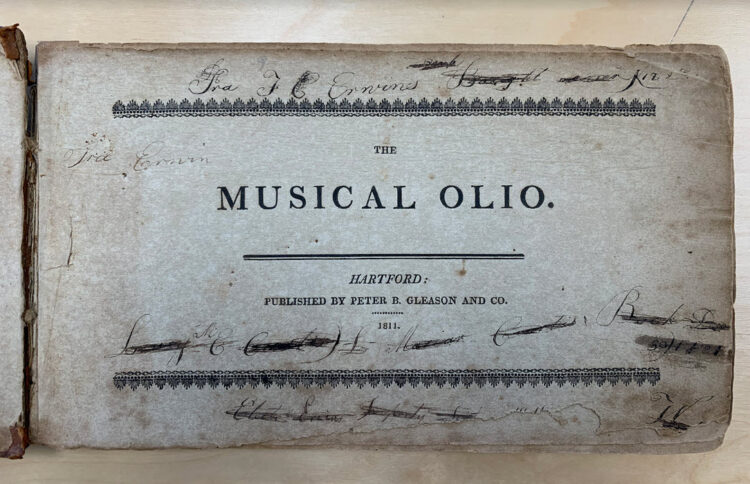

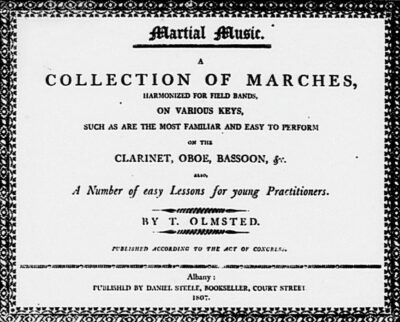

Together with so many others from Connecticut in the early 19th-century, Olmsted and his family relocated to Western New York in 1804. They settled in Whitestown, where they were, probably by no coincidence, less than 7 miles away from Olmsted’s old bandmate, Stephen Moulton. During his time in Whitestown, Olmsted completed and published three collections of original and selected music: The Musical Olio, published in 1805 by Andrew Wright, Northampton, Mass.; Martial Music, published in 1807 by Daniel Steele, Albany, NY; and a second edition of The Musical Olio, published in 1811 by both Samuel Green, New London, Conn., and Peter B. Gleason and Co., Hartford, Conn. In these works Olmsted demonstrates a desire to connect himself with the wider musical world, and notably to encourage instrumental music making. The foreword to the first edition of the Musical Olio reads:

“… I have thought best to print [this music] in characters universally made use of; having not as yet been made to perceive the utility of the simplifications, and new inventions; which are so frequently presented to us for our improvement, by many of our modern masters; — These characters are not only our old acquaintance, but that of the whole musical world; in which all nations can read, and probably will never discard. The instrumental performer may now join with the vocal, and find music in familiar key and good style… That this small volume may prove to be useful in the Church, and entertaining in the Chamber, is the ardent wish of The Compiler.”

Numerous advertisements for Olmsted’s editions of The Musical Olio can be found in newspapers published as late as 1818, while ads for Martial Music disappear by 1809. Contributing to The Music Olios’ popularity is undoubtedly the fact that these works are part of a tradition of published American psalmody that goes back to the mid-18th century. Olmsted’s Martial Music, on the other hand, offers the public something entirely unique.

Other compilations of military music by Oliver Shaw and Samuel Holyoke appeared in the United States during this decade, but what sets Olmsted’s work apart is that its author had actual experience as a bandsman in the Continental Army. Because of this, Martial Music is the only direct source that offers firsthand insight into what pieces belonged to the repertoire of American military bands during the War for Independence. Of the 57 pieces included in the compilation, 11 are explicitly attributed to “T. O.” or “T. Olmsted,” and 3 marches are drawn from British General John Reid’s “A Set of Marches,” published in 1778 by R. Bremner, London. While the collection also includes more contemporary works for the year of publication, such as Jefferson’s March, Hail Columbia, and Gen. Hamilton’s Dead March, notable selections that were likely taken from Olmsted’s war experience include: Col. Webb’s Slow March, The British Grenadiers, Handel’s Dead March in Saul, and Washington’s March (a tune reappropriated during the war from Britain’s 17th Regiment of Foot).

The Later Years, 1813–1848

Following Alice’s death in 1813, and potentially unsettled by early American failures on the borders between Canada and New York in the first year of the War of 1812 (1812–1815), Olmsted moved back to Connecticut. Between August 9 and 12, 1814, a British naval squadron made efforts to secure a foothold in Connecticut through the bombardment of Stonington, but ultimately failed to occupy the city. With the military threat once again so close to home, Olmsted appears in the muster rolls one last time, serving with the militia in New London from August 18 until October 24.

The information we have on the last quarter of Olmsted’s life comes almost entirely from government pension records. In 1818, a full 35 years after the Treaty of Paris, Congress passed “An act to provide for certain persons engaged in the land and naval service of the United States, in the revolutionary war.” Olmsted was one of the thousands of aging veterans, and widows of veterans, who applied for much needed financial assistance.

It was common for pension applications to include affidavits from friends and community members testifying on behalf of the veterans. Olmsted’s application included a statement co-signed by one of his former bandmates, John Steele, that ended with a plea for aid, “Olmsted… needs the assistance of his Country for support.” Despite his efforts to recover financially, Olmsted’s “many losses and disappointments” had continued through the 1810s.

In 1820, Congress revised the pension act. Fearing that their previously approved payment scheme was being taken advantage of, Congress made veterans and their families resubmit their applications, requiring that the new applications demonstrate economic need in a list of the applicant’s “whole estate and income.” Olmsted had no list:

“He has no family with him and is entirely destitute of Property excepting his wearing apparel which is no more than decent, he is in a poor state of health one of his legs has been broken and renders him a cripple for life. He has been a farmer and an instructor of Music but now unable to labour or obtain a livelihood by either occupation—”

The exact circumstances of Olmsted’s destitution are unknown, but by 1822 his situation was so dire that his sons rather seriously intervened: “Ralph Olmsted & Francis Olmsted [,] Sons of Timothy Olmsted [,] showing that Timothy Olmsted… is a distracted person & his estate [etc.] is incapable of taking care of him Self praying the Court to appoint a Conservator to Said Timothy…” The application was approved.

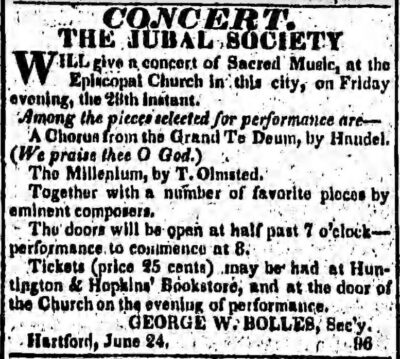

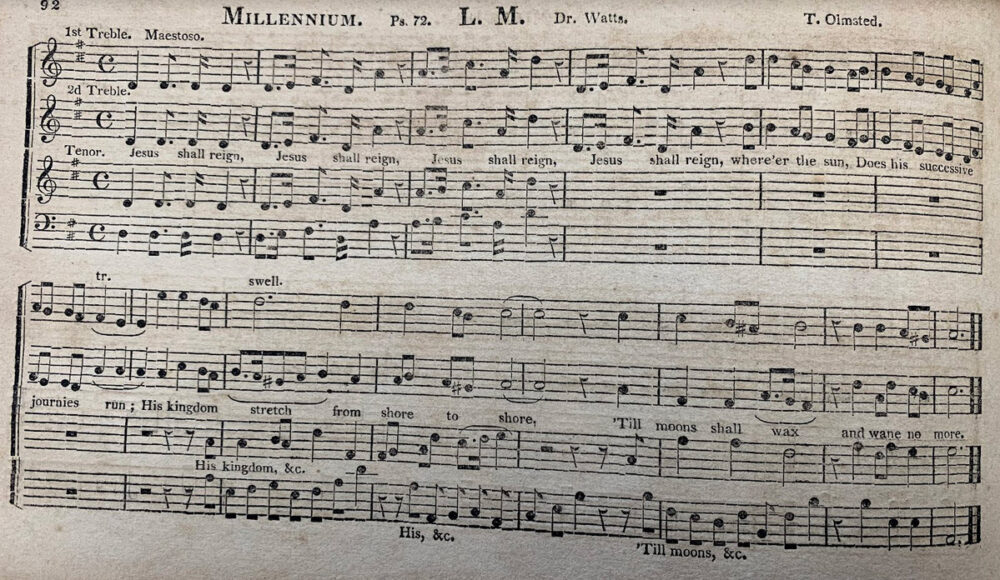

In the face of what appeared to be overwhelming financial hardship, Olmsted and his music lived on. That same year the Jubal Society of Hartford advertised for “a concert of Sacred Music,” in which only two pieces and composers were listed by name: “A Chorus from the Grand Te Deum, by Handel” and “The Millenium, by T. Olmsted.” The next year, two accounts of Olmsted leading concerts appeared in the Hartford Courant. On May 7, 1823, Olmsted directed a choral concert that clearly impressed the correspondent, “We think the performance was never equalled in this state.” One month later, Olmsted led another choral concert in Hartford. The review of this performance gives us a rare insight into Olmsted’s sensitivity as a leader and cosmopolitan taste in repertoire:

“The choir of the First Ecclesiastical Society of this city afforded the amateurs of music a rich repast on Tuesday evening. Mr. Olmsted, who led on this occasion, discovered much taste in the selection of pieces. The works of Handel, Haydn, and Mozart will always be favourties with those who have any taste for the charms of music. In this performance, the choir seemed sensible that loudness of sound was less essential than expression… We hope this musical choir will continue their exertions to improve the public judgment and taste in this delightful science. A very numerous audience expressed their satisfaction, by their silence and giving a listening ear.” – Hartford Courant, Hartford, Connecticut, June 3, 1823

Olmsted lived in Hartford County for the next twenty years. In 1843, Olmsted’s son-in-law, Hezekiah Barnes, began the process of transferring Olmsted’s pension payments to New York, and Olmsted made his final move. Perhaps living with his son, also Timothy Olmsted, or with his daughter Caroline and her husband Hezekiah, Olmsted lived out the last five years of his life in Phoenix, in upstate New York, about halfway between Syracuse and Lake Ontario. On February 5, 1848, Timothy Olmsted passed away at the age of 88.

Self-promotion was never Olmsted’s strength, and after 1848 his already fading legacy was entirely in the hands of the public. Despite his remarkable longevity and devotion to craft, each advancing year pushed his music further into obscurity. Nevertheless, his impact was felt amongst those of his own generation. In 1854, self-described “old folks” of Hartford wrote an impassioned letter to the editor of the Hartford Courant proudly asserting that, “Timothy Olmsted was the Mozart of America.” This, however, would be the last and most extreme defense of Olmsted’s reputation. Within a decade of his passing, his once celebrated music could be heard no more, and his pioneering career forgotten.

Dominic Giardino is the Executive Director of Arizona Early Music, a historical clarinetist, and researcher of military music in the early Atlantic World. He can be heard on albums recorded by Three Notch’d Road: The Virginia Baroque Ensemble and Newberry’s Victorian Cornet Band.

Others in the series: