by Áine Palmer

Published January 13, 2025

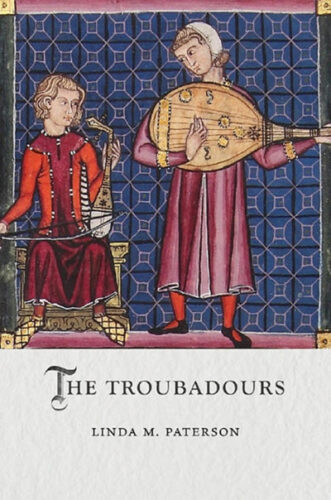

The Troubadours by Linda M. Paterson, Reaktion Books, 2024. 256 pages.

Everyone knows the troubadours, or, at least, has a fuzzy idea about what a troubadour is. For some the name might conjure images of traveling singer-songwriters from long, long ago; others are more likely to think of the 1960s folk revival. While contemporary figures like Leonin and Perotin, Petrus de Cruce, or even “the trouvères” mean little to people outside the world of early-music aficionados, the troubadours, oddly, remain in our contemporary lexicon. The moniker continues to hold vague associations with wandering bards professing their love to unattainable ladies. But who were the troubadours, really?

In The Troubadours, Linda M. Paterson’s delightfully accessible introduction to these poet-composers of yore, we can start to answer that question. Troubadour song, written in Old Occitan, was largely composed in the 12th century and represents some of the earliest European vernacular literature put down in writing. Surprisingly, we have the names of hundreds of troubadours. While Medieval music in the 12th and 13th centuries was generally transmitted anonymously, the extravagant songbooks that document troubadour song (known as chansonniers) make quite the song and dance about who these composers were, even going so far as to include short biographies alongside their songs (known as vidas).

Paterson’s book tells the story of this musical tradition by following the stories of the poet-composers themselves. The Troubadours begins with Guilhem IX, widely credited with being the first troubadour, and ends in the early 13th century with the Cathars heresy — a heterodox religious movement that precipitated the so-called Albigensian Crusades, causing Northern French armies to invade the Southern Pays d’Oc. Between these two poles, Paterson presents concise studies of some of the most famous troubadours, offering thoughtful observations on poetic style alongside vivid descriptions of the historical context that shaped the tradition.

In this sense, the book essentially amounts to a rather old-fashioned form of music history writing: It is a collection on the lives and works of these medieval composers. While recent decades have seen the field of music history benefit hugely from studies that focus on performers, audiences, and institutions, Paterson provides a compelling case for the value of biography when considering the songs of the past. Each case study considers what the limited extant evidence can tell us about these historical figures and sets analyses of individual style against the backdrop of the broader tradition.

This approach has the benefit of allowing us to pick apart the tangled threads of poetic convention and subjective experience, while still getting to enjoy the — often delightfully juicy — biographical anecdotes that have been passed down in the chansonniers. Paterson’s selection is necessarily limited: We have the names of over 450 troubadours, far too many to be reasonably discussed in a single volume. However, this book provides a satisfying glimpse of the diverse lives of these medieval songwriters.

Some troubadours, like Guilhem IX, were noblemen. Others were base born, like Marcabru (the topic of chapter three). The corpus is largely dominated by men, but chapter five is importantly devoted to the trobairitz — the roughly 20 women who wrote songs (which is to say, the women who participated in the tradition for whom we have names).

Throughout the book, Paterson engages with a range of genres and styles, including the elusive trobar clus (addressed in chapter six on Arnaut Daniel), and the genre of the political sirventois, as written by Betran de Born (chapter seven). Engaging with the troubadours through biography also creates a natural space for Paterson to discuss some of the major historical events that shaped their lives and, consequently, the songs, and The Troubadours includes lucid discussions of the complex conflicts between France and England in this period as well as the Cathar heresy.

Paterson’s book is a welcome addition to the current available literature on the subject. Its clarity makes it an ideal introductory text, as suitable for the undergraduate classroom as it is for the armchair historian. Some might miss the paratextual apparatus of academic monographs — for example, save a few exceptions, songs are included in English translation alone. While this (without a doubt) makes for a less intimidating read, many may miss the opportunity to engage with the original texts, even if just for the fact that the absence of Occitan incipits may make finding recordings of the songs discussed challenging.

Citations are generally sparse, and Paterson’s engagement with secondary sources feels occasionally uncritical. Additionally, much information — such as, for example, the shelf marks and folio numbers of the manuscript illuminations which beautifully illustrate the book — is tucked out of immediate sight and must be hunted for in the back of the volume. Ultimately, these are decisions made with accessibility in mind; Paterson’s expert handling of the material offers a wonderful introduction to this material. One hopes that further engagement with the songs and their sources isn’t discouraged by a lack of signposts in the text itself.

The Troubadours deftly brings to life the lives, songs, and historical context of a set of figures who have long been considered foundational in Western music history. The book is beautifully presented with numerous full-color illuminations and will, with any luck, introduce many curious minds to these poet-composers from so many centuries ago.

Áine Palmer is a PhD candidate at Yale University and will be a visiting scholar at KU Leuven in 2025 under the support of the Belgian American Education Foundation Fellowship. Her research considers the intellectual and material contexts of Medieval song, and she is currently completing a dissertation on trouvère songbooks.