by Charlotte Mattax Moersch

Published February 11, 2023

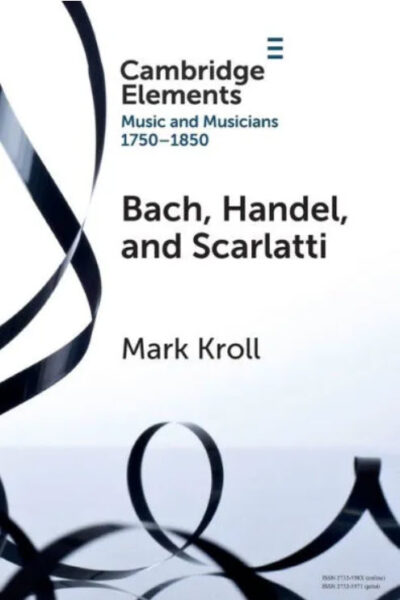

Bach, Handel, and Scarlatti: Reception in Britain 1750-1850 by Mark Kroll. Part of the Cambridge Elements: Music and Musicians, 1750-1850 series. Cambridge University Press, 2022. 81 pages.

In this entertaining, informative book, Mark Kroll provides a vivid account of performances of the music of Bach, Handel, and Scarlatti in Great Britain between 1750 and 1850. Seeking to debunk the notion that musicians at this time were not interested in music of the past, he presents convincing evidence to the contrary, drawing from an impressive breadth of archival records.

In this entertaining, informative book, Mark Kroll provides a vivid account of performances of the music of Bach, Handel, and Scarlatti in Great Britain between 1750 and 1850. Seeking to debunk the notion that musicians at this time were not interested in music of the past, he presents convincing evidence to the contrary, drawing from an impressive breadth of archival records.

Kroll notes that concerts of early music were not exclusive to Great Britain, citing the concerts historiques presented by Francois-Joseph Fétis at the Paris Conservatoire in 1832, and the historischen Konzerte given by Felix Mendelssohn at the Leipzig Gewanthaus in 1838, 1841, and 1847. However, British enthusiasm for old music, particularly that by Handel, Bach, and Scarlatti—all born in 1685—was unsurpassed, with more performances and publications of music by these three composers in Great Britain than any other country during this period.

Following an insightful introduction, in which he examines the political, cultural, and aesthetic reasons for British dominance in the area of early-music performance, Kroll provides a section on each composer. He brings together a trove of valuable information, interweaving accounts of concerts, publications, music manuscripts, and pedagogical treatises with amusing anecdotes from contemporary diaries and letters. Each section concludes with a brief look into musical activity relevant to Bach, Handel, and Scarlatti after 1750. Four valuable appendices present records of this era’s performances.

Many scholars and performers today may be unaware of the importance of foreign composers and performers to Britain’s early-music revival. The German musicians Johann Christian Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel introduced the music of J.S. Bach into the British musical mainstream, a legacy later cemented by Felix Mendelssohn and Ignaz Moscheles, while the Italian immigrant Muzio Clementi promoted the music of Scarlatti, Handel, and Bach, setting the stage for its popularity in Britain during the 18th and 19th centuries. Augustus Frederic Christopher Kollmann, arriving in London in 1782, published numerous compositions by Bach in his Essay on Practical Musical Composition (1799).

Native Britons played a large role in disseminating this music as well. For example, the first complete English edition of The Well-Tempered Clavier was published in 1810 by Samuel Wesley, who did much to foster the music of Bach in Britain at this time, playing concerts in important venues such as Covent Garden and the Hanover Square Rooms. A decade later, Thomas Boosey published the first English translation of Forkel’s biography of Bach.

Through quotes from diaries and newspapers, Kroll sketches a vibrant portrait of concert life in Britain. For example, in his diary, Moscheles writes about the lavishness of the Handel commemoration of 1834 that included “625 musicians—223 instrumentalists, a chorus of 397 singers, and five soloists—performing for an audience of 2700.” According to Moscheles, newspapers published reports of “several ladies weeping, and some actually fainting,” and confided that he was “deeply moved by these sounds.” As Kroll notes, it is not surprising that the royal family embraced these concerts, which gave the monarchy a platform for displaying its power and wealth.

Kroll also provides information about the obstacles musicians sometimes faced in presenting this music. He traces Britain’s slow acceptance of Bach to the diarist Charles Burney, who disparaged his music as “extremely difficult,” disapproving of Bach’s thick, contrapuntal textures and fugue subjects, preferring Handel’s more accessible tunes. Prejudice against Bach continued into the 19th century. Like Burney, William Crotch could not suppress the urge to compare Bach to Handel, whom he considered the better composer: “Bach became the Michael Angelo of our art, as Handel was our Raffaelle…Raffaelle is generally acknowledged to be the greatest of painters…Handel may thus be preferred, because his vocal music and choruses are superior to Bach’s….”

Along with prejudice, misconceptions and contemporary aesthetics sometimes plagued the early-music revival. Kroll notes that, in the decades after 1750, Scarlatti’s music was disseminated largely in idiosyncratic transcriptions such as Charles Avison’s concerto grosso transcriptions for strings. Arrangements of Handel’s operas were also plentiful, although the practice was often denigrated. An 1828 account in the Athenaeum about Rossini’s opera Semiramide recounts: “No sooner is an opera out, but to instant work fall the legions of arrangers and adapters. Out comes Semiramide, arranged for the pianoforte, and for aught we know, Semiramide arranged for the French horn or the Jew’s-harp.”

After 1800, the public began to tire of Handel’s lengthy oratorios, so performing excerpts became commonplace. Kroll notes that, between 1818 and 1895, the Royal Philharmonic “did not present a single performance of a complete oratorio or any Handel vocal work—only excerpts.” Other unusual practices related to Bach’s organ works. Until the late 18th century, few organs in Britain had full pedal boards, so performers had to adapt. The author recounts that “Mendelssohn therefore often had to revert to the two-player approach when he performed Bach’s organ music in Britain.” He recounts an 1833 performance in which the pianist Johann Baptist Cramer played the pedal line while Mendelssohn played the keyboard parts.

Even in performances that adhered to the original text, a composer’s intentions could be misconstrued. For example, we learn that, in his 1837 historical soirées, Moscheles played Scarlatti sonatas on a Schudi-Broadwood harpsichord, which his wife Charlotte said was built in 1771. Although Moscheles complained about the “thin” sound of the harpsichord, he liked the “Venetian swell stop,” which he admired for “the greater sonority…given to the tone.” He misunderstood the use of the two manuals, thinking that crossed-hand passages should be played on separate manuals.

Kroll’s short study brings this wide variety of source material together for the first time, giving us a glimpse into the intriguing history of the music’s reception and the aesthetics guiding British interest in early music during this period.

Charlotte Mattax Moersch, professor of harpsichord and musicology at the University of Illinois, has recorded the solo harpsichord pieces of Noblet, Février, D’Anglebert, A-L Couperin, and Bach. Recent videos include The Vernissage Project.