by Stephanie Manning

Published February 20, 2023

LOVESICK, countertenor Randall Scotting and lutenist Stephen Stubbs. Signum Classics SIGCD736

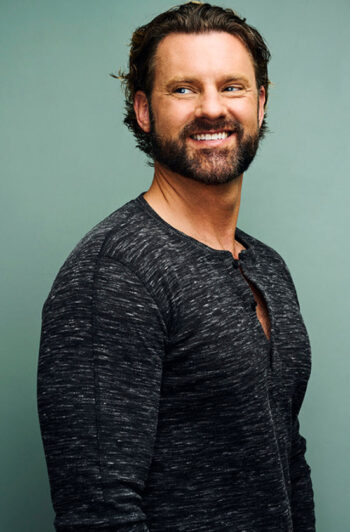

Valentine’s Day has come and gone, and for those feeling oversaturated with sappy love songs, Randall Scotting has a remedy. LOVESICK, the American countertenor’s latest album and collaboration with lutenist Stephen Stubbs, provides 17th-century perspectives on heartbreak, longing, and loneliness.

In just under an hour, LOVESICK traces a loose narrative arc through 22 short selections, each ranging between one and four minutes. The English, Italian, and French composers are for the most part familiar — like John Dowland, Pierre Guédron, and Marc’ Antonio Cesti — with the exception of the Italian Daniele de Castrovillari, included here with “Luci belle” from his opera La Cleopatra. Mixed into these selections are a number of traditional folk tunes, adding a touch of variety that blends in easily with the rest of the album.

Scotting succeeds in accentuating the passion and drama in these songs. His flexible countertenor is perfectly suited to the task, with a warm tone, crisp enunciation, and a natural vibrato that is far from distracting. Moments of extra flair are memorable without being over the top—a crisply-rolled “r” here, a slight slide between pitches there.

Henry Lawes’ “I rise and grieve” demands the vocalist’s widest range, which he delivers with technical agility and aplomb, and Henry Purcell’s “When Orpheus sang all nature did rejoice” gives us the first taste of his rich low register in a brief but memorable descending passage. This selection is short but it packs a punch, playing up both the dynamics and the drama. For a longer exploration of his low register, look no further than “At the mid hour of night,” a traditional Irish song arranged by John Pyke Hullah.

Throughout, Stubbs remains a steady background presence, responding to his singer’s energy without drawing undue attention. Purcell’s “She loves and she confesses too emerges” as a great example, where the work’s bouncy triple meter benefits from his energetic strumming.

Three solo interludes briefly spotlight his different instruments: Baroque guitar (built by Ivo Magherini) in the peppy Suite from King Arthur, a 10-course Renaissance lute (by Stephen Barber) in Complaint: “Fortune my foe,” and 10-course bass lute (by Lawrence K. Brown) in “Packington’s Pound.” With a pair of good headphones, you hear that the microphones have picked up on his breathing—an interesting performance insight, though never too distracting.

As the album goes on, the mood becomes more melancholy and resigned. Shortly after the bittersweet “Mary’s dream” (traditional Scottish, arranged by Richard Langdon) comes the gloomy “The Three Ravens” (traditional English, arranged by Thomas Ravenscroft). As elsewhere throughout the album, the intensity of Scotting’s performance here keeps the repetitive lyrics and melody from becoming sterile. He saves his most haunting performance for “Black is the color of my true love’s hair” (traditional Scottish, arranged by John Jacob Niles), where the topic of true love feels the most heartbreaking.

But perhaps there is a light at the end of this love tunnel. The final song, Purcell’s “O solitude, my sweetest choice,” dismisses the need for love in favor of becoming content with one’s own company. Maybe the only date you need is yourself.

Stephanie Manning is a regular correspondent for ClevelandClassical.com and served as a fellow at the 2022 Rubin Institute for Music Criticism. As a bassoonist, she is in her final year of study at Oberlin Conservatory.